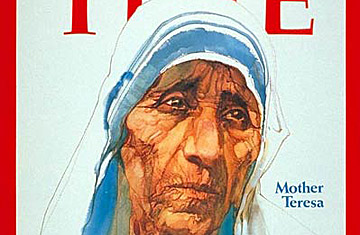

Mother Teresa

(5 of 10)

Nirmal Hriday is now only one of 32 havens for the dying, 67 leprosariums, 28 children's homes that the order runs round the world, but it still moves visitors to wonderment. Muggeridge claims a modern sort of miracle for it. Some photos shot in the infirmary's hopelessly dim light, he says, turned out to be bathed in an inexplicably soft glow. Calcutta Journalist Desmond Doig, a self-described skeptic and author of a forthcoming book on Mother Teresa, reports a more personal miracle. Instead of finding the place repugnant, he became so suffused with its compassion that he began to nurse the patients himself. "Our work," explains Mother Teresa, "brings people face to face with love."

Not at Nirmal Hriday nor any other of Mother Teresa's homes does anyone get a sectarian hard sell. The dying get the rituals they want: Ganges water on the lips for the Hindu, readings from the Koran for the Moslem, last rites for the occasional Catholic. Babies left at Shishu Bhavan, the busy Calcutta center that feeds the hungry and shelters abandoned children, remain Moslems or Hindus if the parents wish; only foundlings are baptized. The nun who runs the center conspiratorially reveals that the sisters have saved more than one Hindu marriage from family pressure by quietly providing a childless couple with a newborn baby to pass off as their own.

Such understanding of local ways is typical of Mother Teresa, who became a citizen of India in 1948. But her Catholic orthodoxy does not bend far. Though the sisters operate 28 family-planning centers in India and elsewhere round the world, the only birth control they offer is the papally-approved rhythm method. As for abortion, Mother Teresa calls it a crime that kills not only the child but the consciences of all involved.

Mother Teresa and her sisters are not without their critics. To some, the nuns and brothers are merely bandaging a civic wound that needs drastic surgery. "We are not trying so much to do social work," Mother Teresa explains, "as to live out that life of love, of compassion, that God has for his people." The poor, she says, suffer even more from rejection than material want. "If we didn't discard them they would not be poor. An alcoholic in Australia told me that when he is walking along the street he hears the footsteps of everyone coming toward him or passing him becoming faster. Loneliness and the feeling of being unwanted is the most terrible poverty."

However deep her compassion for the poor, Mother Teresa nurses no hatred for the rich. She joyfully shows a scrapbook of pictures of orphans she has placed in affluent homes in the U.S. and Europe. But she is also alert to the perils of contemporary civilization. "Our intellect and other gifts have been given to be used for God's greater glory," she says, "but sometimes they become the very god for us. That is the saddest part: we are losing our balance when this happens. We must free ourselves to be filled by God. Even God cannot fill what is full."