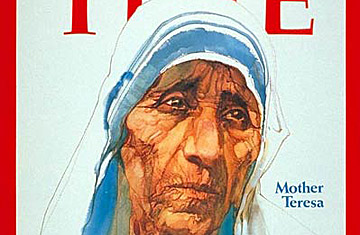

Mother Teresa

(10 of 10)

The great religions of the East, Hinduism and Buddhism, have never swung away from mysticism as the pinnacle of holiness, though they also value deeds of compassion. Traditional Islamic belief views the saint or wali (friend of God) as a person with a foot in both worlds—one whose special communion with Allah coincides with his excellence in good works. As for Christianity's own rich tradition of monastic mysticism, which goes back to the fabled desert anchorites of Egypt, it seems to be undergoing a revival there and elsewhere.

In the ancient monastery of Deir el Makarios in the desert 50 miles southwest of Cairo, a Coptic monk is causing a mild sensation, drawing as many as 500 visitors a day. His name: Matta el Meskin, Matthew the Poor. Like the great anchorite St. Anthony, Matta el Meskin was once an affluent young man—a prosperous pharmacist. At the age of 29, heeding Jesus' call to "sell what you have," he disposed of his two houses, two cars, two pharmacies, gave the proceeds to the poor and, keeping only a cloak, devoted himself to prayer and asceticism. He is out of the world and yet still of it. From his cell, where he lives mainly on bread and water, he has written more than 40 books and pamphlets, most of them scholarly books on church affairs, directed the total rehabilitation of the decaying monastery and begun a reformation of Coptic monastic life so profound that he was one of three nominees to be Coptic Pope in the 1971 election.

Western Christians often mention Brother Roger Schutz, founder of France's Protestant monastery of Taize (TIME, April 29, 1974), as a saint. Brother Roger's worldwide Taize youth groups are out to change the world, but what he offers at Taize —and to them—is essentially a shared life based deeply on prayer. "We should not pray for any useful end," Brother Roger has written, "but in order to create a community of free men with Christ."

Most living saints, activists or no, of course do get down on their knees and pray, some for hours a day. In the traditional concept of sainthood, in fact, prayer is an essential condition of sanctity, the key to the deeds that surround it. Most of today's saintly people would agree that the concept has not changed.

"To keep a lamp burning," Mother Teresa told Correspondent Shepherd, "we have to keep putting oil in it." To build her own faith, she said, "I had to struggle, I had to pray, I had to make sacrifices before I could say 'yes' to God."

Those who succeed, however, share something of a revelation.

Schwester Selma of Jerusalem cherishes a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, the great Bengali poet of Calcutta, that perhaps says it best:

I slept and dreamt That life was joy I awoke and saw That life was duty I acted and behold Duty was joy.

That may be a liberating truth. Perhaps, in a world that celebrates this season with more than a touch of hedonism, it is just the corrective message that the saints among us bring.