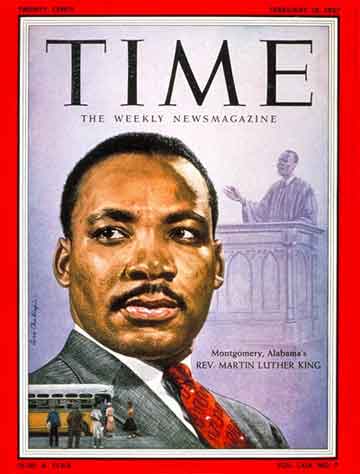

Montgomery Alabama's Rev. Martin Luther King

(5 of 10)

Overnight the word flashed throughout the various Negro neighborhoods: support Rosa Parks; don't ride the buses Monday. Within 48 hours mimeographed leaflets (authorship unknown) were out, calling for a one-day bus boycott. A white woman saw one of the leaflets and called the Montgomery Advertiser, demanding that it print the story "to show what the niggers are up to." The Advertiser did—and publicized the boycott plan among Negroes in a way that they themselves never could have achieved. The results were astonishing: on Monday Montgomery Negroes walked, rode mules, drove horse-drawn buggies, traveled to work in private cars. The strike was 90% effective.

How They Did It. On the day of the strike, some two dozen Negro ministers decided to push for continuance of the bus boycott. The original demands were mild: 1) Negroes would still be seated from the rear and whites from the front, but on a first-come-first-served basis; 2) Negroes would get courteous treatment; 3) Negro drivers would be employed for routes through predominantly Negro areas. To direct their protest, the Negro ministers decided to form the Montgomery Improvement Association. And for president they elected the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., a relative newcomer whose ability was evident and whose newness placed him above the old feuds. That night, at a hastily called mass meeting, more than 5,000 Negroes approved the ministers' decisions.

Slowly the boycott took permanent shape. More than 200 volunteers offered the use of their cars; nearly 100 pickup stations were established. Church and mass-meeting collections kept the Montgomery Improvement Association alive at first; then donations began to flood in from across the U.S. and from as far away as Tokyo. By the end of last year the M.I.A. had spent an estimated $225,000. At every turn King outgeneraled Montgomery's white officials. Example: the officials went to court to have the M.I.A.'s assets frozen, but King had the funds scattered around in out-of-reach banks that included half a dozen in the North.

Get Tough. Montgomery's whites reacted complacently. The city commission went through the barest motions of offering compromises, e.g., the Negroes were promised that the bus drivers would show them "partial courtesy." Mayor W. A. ("Tacky") Gayle appointed a committee to negotiate with the Negroes—and named as a member the head of the local White Citizens' Council.

The Negroes stood firm, and white complacency turned to fury. Rumors were spread that boycott leaders had used mass-meeting funds to buy themselves Cadillacs. Older Negro preachers were taunted for having yielded their seniority to a young whippersnapper. To lure the Negroes back onto the buses, the Montgomery city commission called in three hand-picked Negro ministers (who had been on the edges of the boycott) and persuaded them to agree to settlement terms that had little if any practical meaning. The commission's plan was to announce the settlement in Sunday's papers, but Saturday night word of the plan reached King (who was tipped off by a long-distance call from a Minneapolis reporter who had seen the story on the Associated Press wire). King and his top M.I.A. associates spent most of the night going from tavern to tavern warning Negroes that there had been no real settlement.