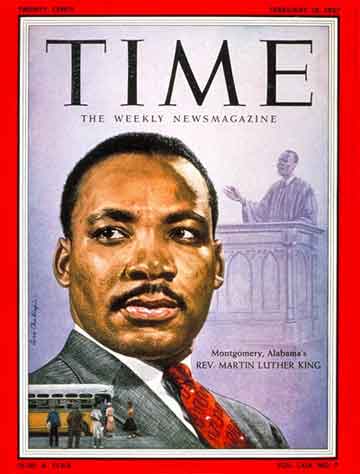

Montgomery Alabama's Rev. Martin Luther King

(4 of 10)

Aching Feet. Snuggled against a hairpin bend in the meandering Alabama River, Montgomery was a city where 80,000 whites pretty generally believed there was no problem with 50,000 Negroes. Working mostly as farm hands or domestic servants for $15 or $20 a week, Montgomery's Negroes had neither geographic nor political unity. There was no concentration of Negroes in one area; instead, they were split up in neighborhood pockets scattered the length and the breadth of the city. Served by a lackadaisical Negro weekly paper, they had no ready means of communication. More than that, says Martin King, the "vital liaison between Negroes and whites was totally lacking. There was not even a ministerial alliance to bring white and colored clergymen together. This is important. If there had been some communication between the races, we might have got some help from the responsible whites, and our protest might not have been necessary."

Frustrated at every turn, the Negroes had long since fallen to quarreling among themselves in bitter factionalism. "If," says King, "you had asked me the day before our protest began whether any action could or would have been taken by the Negroes, I'd have said no. Then, all of a sudden, unity developed."

It came about through the aching feet of a Negro woman.

In the early evening of Thursday, Dec. 1, 1955, a Montgomery City Lines bus rolled through Court Square and headed for its next stop in front of the Empire Theater. Aboard were 24 Negroes, seated from the rear toward the front, and twelve whites, seated from front to back. At the Empire Theater stop, six whites boarded the bus. The driver, as usual, walked back and asked the foremost Negroes to get up and stand so the whites could sit. Three Negroes obeyed—but Mrs. Rosa Parks, a seamstress who had once been a local secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, did the unexpected. She refused.

"I don't really know why I wouldn't move," says Rosa Parks. "There was no plot or plan at all. I was just tired from shopping. My feet hurt." Rosa Parks was arrested and in the due course of time fined $10 and costs for violating a state law requiring bus passengers to follow drivers' seating assignments.

What They Were Up To. Other Negroes had suffered worse indignities, but hers was the one that the South would long remember. The Montgomery City Lines Inc. had long been a special irritant to the Negroes, who made up 70% of its patronage. At best, they had to pay their fares in front, get off and board again in the rear; sometimes after they had dropped their money in the fare box and were going around to the rear, the bus drivers drove off. At worst, the Negroes were cursed, slapped and kicked by the white drivers. By the time of the Parks case, they had had all they could take without some sort of reply.