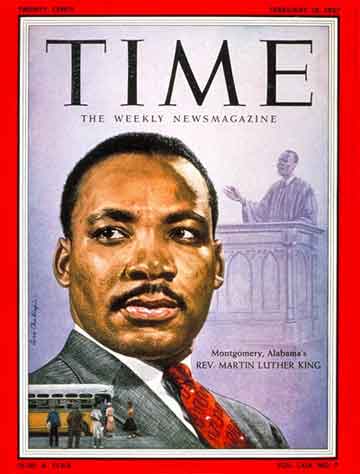

Montgomery Alabama's Rev. Martin Luther King

(2 of 10)

Judicial Recognition. Sturdy (5 ft. 7 in., 164 lbs.), soft-voiced Martin Luther King describes himself as "an ambivert—half introvert and half extrovert." He can draw within himself for long, single-minded concentration on his people's problems, and then exert the force of personality and conviction that makes him a public leader. No radical, he avoids the excesses of radicalism, e.g., he recognized economic reprisal as a weapon that could get out of hand, kept the Montgomery boycott focused on the immediate goal of bus integration, restrained his followers from declaring sanctions against any white merchant or tradesman who offended them. King is an expert organizer, to the extent that during the bus boycott the hastily assembled Negro car pool under his direction achieved even judicial recognition as a full-fledged transit system. Personally humble, articulate, and of high educational attainment, Martin Luther King Jr. is, in fact, what many a Negro—and, were it not for his color, many a white—would like to be.

Even King's name is meaningful: he was baptized Michael Luther King, son of the Rev. Michael Luther King Sr., then and now pastor of Atlanta's big (4,000 members) Ebenezer Baptist Church. He was six when King Sr. decided to take on, for himself and his son, the full name of the Protestant reformer. Says young King: "Both father and I have fought all our lives for reform, and perhaps we've earned our right to the name."

Perched on a bluff overlooking Atlanta's business district, the two-story yellow brick King home was a happy one, where Christianity was a way of life. Each day began and ended with family prayer. Martin was required to learn Scriptural verse for recitation at evening meals. He went to Sunday school, morning and evening services. He was taught to hold Old Testament respect for the law, but it was the New Testament's gentleness that came to have everyday application in his life.

"Never a Spectator." From his earliest memory Martin King has had a strong aversion to violence in all its forms. The school bully walloped him; Martin did not fight back. His younger brother flailed away at him; Martin stood and took it. A white woman in a store slapped him, crying, "You're the nigger who stepped on my foot." Martin said nothing. Cowardice? If so, it would come as a surprise to Montgomery, where Martin Luther King has unflinchingly faced the possibility of violent death for months.

The shabby, overcrowded Negro schools in Atlanta were no match for the keen, probing ("I like to get in over my head, then bother people with questions") mind of Martin King; he leapfrogged through high school in two years, was ready at 15 for Atlanta's Morehouse College, one of the South's Negro colleges. At Morehouse, King worked with the city's Intercollegiate Council, an integrated group, and learned a valuable lesson. "I was ready to resent all the white race," he says. "As I got to see more of white people, my resentment was softened, and a spirit of cooperation took its place. But I never felt like a spectator in the racial problem. I wanted to be involved in the very heart of it."