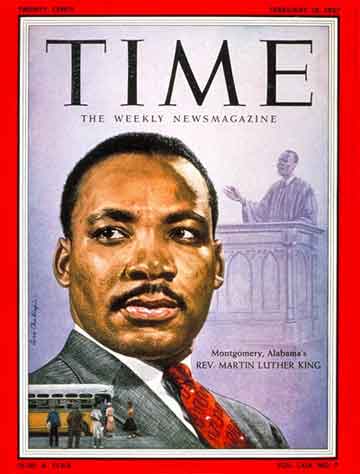

Montgomery Alabama's Rev. Martin Luther King

Across the South—in Atlanta, Mobile, Birmingham, Tallahassee, Miami, New Orleans—Negro leaders look toward Montgomery, Ala., the cradle of the Confederacy, for advice and counsel on how to gain the desegregation that the U.S. Supreme Court has guaranteed them. The man whose word they seek is not a judge, or a lawyer, or a political strategist or a flaming orator. He is a scholarly, 28-year-old Negro Baptist minister, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who in little more than a year has risen from nowhere to become one of the nation's remarkable leaders of men.

In Montgomery, Negroes are riding side by side with whites on integrated buses for the first time in history. They won this right by court order. But their presence is accepted, however reluctantly, by the majority of Montgomery's white citizens because of Martin King and the way he conducted a year-long boycott of the transit system. In terms of concrete victories, this makes King a poor second to the brigade of lawyers who won the big case before the Supreme Court in 1954, and who are now fighting their way from court to court, writ to writ, seeking to build the legal framework for desegregation. But King's leadership extends beyond any single battle: homes and churches were bombed and racial passions rose close to mass violence in Montgomery's year of the boycott, but King reached beyond lawbooks and writs, beyond violence and threats, to win his people—and challenge all people—with a spiritual force that aspired even to ending prejudice in man's mind.

Tortured Souls. "Christian love can bring brotherhood on earth. There is an element of God in every man," said he, after his own home was bombed. "No matter how low one sinks into racial bigotry, he can be redeemed . . . Nonviolence is our testing point. The strong man is the man who can stand up for his rights and not hit back." With such an approach he outflanked the Southern legislators who planted statutory hedgerows against integration for as far as the eye could see. He struck where an attack was least expected, and where it hurt most: at the South's Christian conscience.

Most of all, Baptist King's impact has been felt by the influential white clergy, which could—if it would—help lead the South through a peaceful and orderly transitional period toward the integration that is inevitable. Explains Baptist Minister Will Campbell, onetime chaplain at the University of Mississippi, now a Southern official of the National Council of Churches: "I know of very few white Southern ministers who aren't troubled and don't have admiration for King. They've become tortured souls." Says Baptist Minister William Finlator of Raleigh, N.C.: "King has been working on the guilt conscience of the South. If he can bring us to contrition, that is our hope."