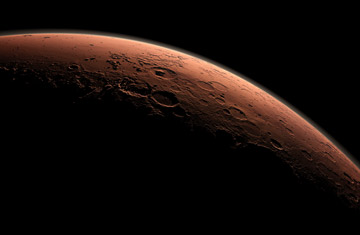

This computer generated view depicts part of Mars at the boundary between darkness and daylight, with an area including Gail Crater beginning to catch morning light.

(5 of 5)

Kennedy, of course, wasn't hamstrung by budget issues, and Obama's space team is quick to point that out. "I would be thrilled if we could land on Mars in the 2030s, and I truly believe that is within the capability of this country," says John Grunsfeld, head of the NASA science directorate and a five-time shuttle astronaut. "I don't believe it is necessarily within the capability of this country with a flat budget."

For the unmanned program, a flat budget would actually be an improvement. Funding for Mars missions is set to fall from $587 million in 2012--that's million, with an m--to $360.8 million in 2013, causing the U.S. to drop out of a planned collaboration with the European Space Agency for two missions, one of which would have returned a sample from the Martian surface. Already in the pipeline is a new NASA orbiter that will launch in 2013, but after that, no missions are scheduled until 2018 and 2020--maybe. Says Grunsfeld: "We can just barely afford those missions."

What any nation can afford, of course, is at least partly a function of what it chooses to afford, even in straitened circumstances. The genius of Kennedy's commitment to a lunar landing before 1970 was its simplicity--a single goal and a deadline. The current plan--with ever changing destinations and dates--has none of that New Frontier clarity.

Kennedy, however, had the help of other Presidents and a cooperative Congress. The space push spanned four Administrations--counting that of Eisenhower, who created NASA--and six Congresses. And while they often scrapped over the budget, they agreed on the goal. A legislature that can barely keep the FAA funded is not an easy partner for any White House with grand ambitions. Space isn't free, but with NASA's budget hovering in the vicinity of just $15 billion per year, or 0.47% of the total federal budget, it's hardly a bank breaker either. The Department of Defense, by contrast, gets $716 billion, or 18.9%. What's more, as with Defense, NASA research pays dividends. The Curiosity program has employed 7,000 high-tech workers in most of the 50 states. And as Grunsfeld points out, the rover's chemical sniffers--sensitive to individual organic molecules--could have national-security applications at ports and airports.

But the extraordinary success of the Mars Curiosity rover masks a far greater truth about space exploration: it requires monomaniacal commitment and an exceedingly high tolerance for failure. In their own way, the JPL peanuts are a reminder of that fact. It's unimaginable in today's attention-deficit political climate that there ever would have been a Ranger 7 after the repeated failures of Rangers 1 through 6. But it took mastering unmanned crash landings before we could master unmanned soft landings. And it took mastering unmanned soft landings before Neil Armstrong--five years almost to the day after Ranger 7 made its suicide plunge into the moon's Sea of Clouds--could set his boot onto the Sea of Tranquility. That's the way science progresses: incrementally, patiently and ultimately spectacularly. Some of America's grandest moments have come when we've trusted that fact.

FOR MORE PICTURES OF THE CURIOSITY PROJECT, GO TO time.com/curiosity