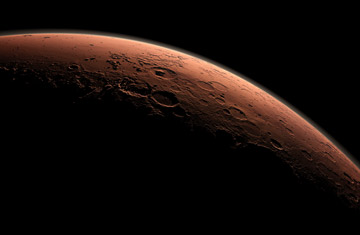

This computer generated view depicts part of Mars at the boundary between darkness and daylight, with an area including Gail Crater beginning to catch morning light.

(2 of 5)

A country that can't get its roads and bridges fixed at home actually has infrastructure on Mars. Two NASA orbiters--Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Odyssey--helped relay Curiosity's transmissions to Earth and wave their newcoming sister in for her landing. And even as Curiosity settles down to work, no fewer than eight other NASA probes are ranging through the solar system, exploring--or on their way to explore--the moon, Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Pluto, the asteroid Ceres and the interstellar void beyond the planets.

It's Curiosity, however, that may be the state of the exploratory art. With 10 instruments weighing a collective 15 times more than those aboard the earlier golf-cart-size rovers Spirit and Opportunity, it will study the geology, chemistry and possible biology of Mars, looking for signs of carbon, methane and other organic fingerprints on a world that a few billion years ago was warm and fairly sloshing with water. The previous rovers and landers have strongly made the case that Martian life--either extant or ancient--is possible, teeing Curiosity up to seal the deal. "We all feel a sense of pressure to do something profound," says geologist and project scientist John Grotzinger.

In some ways, they've already done that, by framing an unavoidable question: If we can do this exceedingly hard thing so well, why do we make such a hash of the challenges at home, the inventing and investing that 21st century progress demands? Help answer that one, and Curiosity could achieve great things on two worlds at once.

Follow the Water

Mars may be a meteor-blasted desert today, but it was once a very different place. Its surface is marked with dry riverbeds, empty sea basins and even dusty oceans. Strip away 99% of Earth's atmosphere and boil off all its water and it would look a lot like its desiccated cousin. Mars was wet for at most a billion of its 4.5 billion years, but as the early Earth proved, that could be enough time to cook up life.

As the generation of Mars ships that began flying in the late 1990s discovered, the surface chemistry of Mars is consistent with a once waterlogged planet. The Spirit and Opportunity rovers used scrapers, drills and abrasion tools to uncover a wealth of minerals that form only or mostly in the presence of water--including salts, gypsum, calcium sulfate and a material known as hematite. The Mars Reconnaissance orbiter found seasonal streaks forming and disappearing on a Martian slope--a sign of underground deposits of existing water that thaw and flow in the Martian spring and freeze and contract in the winter.