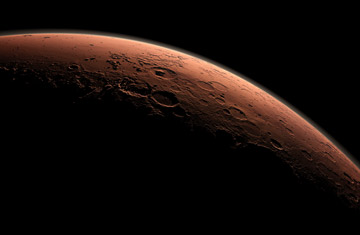

This computer generated view depicts part of Mars at the boundary between darkness and daylight, with an area including Gail Crater beginning to catch morning light.

(4 of 5)

Such anthropomorphizing has always been the case with space in a way it isn't with other scientific endeavors. The confirmation of the Higgs boson earlier this summer was a much bigger development than the Curiosity landing, but few people--outside the physics community, at least--sentimentalized it too much. Nobody calls a particle she.

President Obama--like every President from Kennedy through the second Bush--was quick to make hay out of good news from space. "Tonight, on the planet Mars, the United States of America made history," he said in an official statement. "It proves that even the longest odds are no match for our unique blend of ingenuity and determination." And NASA administrator Charles Bolden Jr.--like every NASA chief who preceded him--was quick to give props to the President who appointed him. "President Obama has laid out a bold vision for sending humans to Mars in the mid-2030s," he said, "and today's landing marks a significant step in achieving this goal."

Expect to hear more of this inspirational talk from both Bolden and Obama in the months ahead, particularly with an election coming and the space-industry state of Florida very much in play. But Obama's record on space has been mixed. The idea of privatizing the business of getting cargo and astronauts to low-earth orbit raised a lot of eyebrows at first, but the move has been looking a lot smarter since Elon Musk's SpaceX Corp. flew a successful resupply mission to the International Space Station in May. SpaceX and a handful of other companies are in line for a lot of paying work flying both manned and unmanned missions for NASA, but it's hard to say how private that effort has really been so far. NASA has shared some of the R&D costs with its candidate companies and signed lucrative contracts with them before they even proved they were up to the job--to the tune of more than $4 billion covered by taxpayers.

The President's plan gets less clear--and less credible--when it comes to manned travel to deep space. NASA is developing a new crew vehicle called Orion--essentially a souped-up Apollo spacecraft--and a new heavy-lift booster dubbed the Space Launch System (SLS), similar to the venerable Saturn V. Returning to the old model of the expendable booster with the crew vehicle perched on top is a safe and smart decision after the disasters of the shuttle era, but that old model was well funded. The first Saturn V was launched in 1967, the 13th and last in 1973, and nine of those rockets took people to the moon.

The SLS, which in one form or another has been in the planning stage since 2004, is not scheduled for its first unmanned flight until 2017 or its first manned one until 2021. After that, it would fly every other year--at best. It's not clear what its destination would be--perhaps an asteroid, perhaps Mars, perhaps somewhere else. "This is a pace that doesn't make any sense," says John Logsdon, professor emeritus at George Washington University's Space Policy Institute. "When Kennedy said he'd get to the moon by the end of the decade, he actually meant 1967, and he thought he'd still be President."