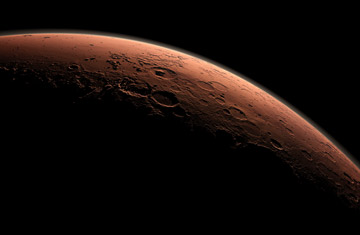

This computer generated view depicts part of Mars at the boundary between darkness and daylight, with an area including Gail Crater beginning to catch morning light.

The folks in mission control at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory ate a lot of peanuts in the minutes leading up to the landing of the Curiosity rover on Mars. Peanuts have been the order of the day at JPL when a spacecraft is preparing to land ever since July 31, 1964, when the Ranger 7 probe was making its final approach to the moon. The Ranger's job was a simple one: to crash-land on the lunar surface, on the way down snapping a few thousand pictures to beam back home. Still, six Rangers before it had failed, and the JPL engineers knew they were about out of chances. Ranger 7 at last broke that losing streak, and as it happened, someone was nibbling peanuts during the landing. That, the missile men of JPL figured, must have been a good-luck charm--and no one's dared defy it since.

But it would take more than luck and peanuts to get Curiosity safely to the surface of Mars. At 1:25 a.m. E.T. on Aug. 6, the SUV-size rover, sealed inside a blunt-bottomed capsule, would slam into the Martian atmosphere at a blazing 13,000 m.p.h. (20,920 km/h). Seven miles (11.3 km) above the surface, when the thin air had slowed the ship to 900 m.p.h. (1,450 km/h), its heat shield would pop away, and it would deploy a billowing parachute. Its retrorockets would then bring the rover and its housing to a near hover just two stories above the surface, where it would be lowered to the ground by wire cables--a $2.5 billion extraterrestrial marionette, settling its wheels gently into the red soil.

In Chicago, the Adler Planetarium held a late-night pajama party so families could follow the landing live. In New York City, crowds gathered in Times Square to watch on a giant screen that usually shows only ads. NASA live-streamed the event, and the traffic was so great--with up to 23 million people watching in the four hours immediately surrounding the landing--that the servers crashed.

What the people watching the live feed saw was not a spacecraft approaching Mars but a roomful of controllers in matching blue shirts, muttering about data acquisition and imager activation and drogue deployment and more. While much of that was incomprehensible, it was clear that something good was building. And then flight-dynamics engineer Allen Chen called, "Stand by for sky crane," and the room fell silent. Less than a minute later, he announced, "Touchdown confirmed! We're safe on Mars!" And with that, the silence was broken--explosively. "That rocked!" exclaimed deputy project manager Richard Cook as he took the stage at the celebratory press conference that followed. "Seriously, was that cool or what?

It was cool indeed, but it was much more too. In an era in which the grind and gridlock of Washington have made citizens wary of anything the government touches, this was a reminder of what the country can still do. The scene in mission control was what smart looks like. It was what vision looks like. Retrorockets could have eased Curiosity straight down to the surface, but that would have stirred up too much dust, perhaps fouling its works before it even got started. So the engineers chose the hard and creative and dangerous solution for the simple reason that it was also the best one.