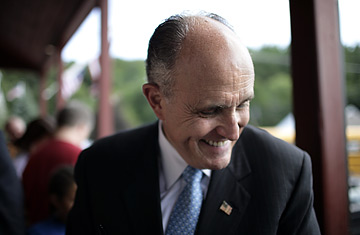

Republican presidential hopeful, former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, visits the Dodge's Store in New Boston, New Hampshire on August 17, 2007.

(4 of 4)

No one could have expected communications to be flawless. "That emergency would have probably overwhelmed any emergency system," notes 9/11 commission staffer Farmer, who was the attorney general for New Jersey under a Republican administration. But Giuliani owns some accountability for the failures. "To say that he had identified problems and he'd been in office for a while and they hadn't been fixed--that's fair," Farmer says. Gorelick, the 9/11 commissioner, says Giuliani's shortcomings became clear when the commission looked at the Pentagon on 9/11. "If you compare the incident command at the Pentagon to the one at the World Trade Center, you will see the difference between life and death," she says. "In New York, the hard decisions were not made. There was not a unity of command. And heroic firefighters went up into the towers when they should have been coming down."

Ministry of Fear

More than anything else, counterterrorism experts interviewed by TIME cited Giuliani's campaign rhetoric as a cause for concern. He frequently conflates different threats, from Iraqi insurgents to al-Qaeda to Iran, into one monolithic dark force. He routinely compares the terrorism threat to the Holocaust and the cold war. In one 15-min. phone interview in August, Giuliani compared the terrorism threat with Nazism or communism six times. When I asked him if he risked exaggerating the threat, since most terrorist plots against the West are not the kind of attacks that will bring down a nation, he replied, "I'm not saying it would take down a country. What terrorism can do and has done is kill thousands and thousands of people. It's real, it's existential, it's independent of us."

Retired Lieut. General William Odom was director of the National Security Agency under Ronald Reagan from 1985 to 1988. He calls Giuliani's terrorism rhetoric "the most delightful thing that al-Qaeda could want." And he laments that Giuliani isn't showing the stoicism he displayed on 9/11. "We need a President who cools it," says Odom, a senior fellow with the conservative Hudson Institute. As for Giuliani's analogy to the cold war, a period Odom knows rather well, he is unimpressed. "Jihadism is a mosquito bite compared to communism," he says. "Anybody who talks about terrorism this way is like a witch doctor."

Giuliani, however, seems to think it is almost impossible to overstate the risk. "We've never had a history of overestimating threats," says the former mayor. "We underestimated by a lot the threat of Nazism." Yet when candidates give terrorists too much credit, they can inadvertently assist them in terrifying the public, says Frank J. Cilluffo, a terrorism expert at George Washington University. "Our words matter," he says. "The last thing we want to do is empower [terrorists] and make them holy warriors, which they're not."

Giuliani used to speak more carefully about terrorism. "No mayor, no Governor, no President can offer anyone perfect security. You've got to be able to deal with a certain level of risk in anything that you do," he said in 1999. On the eve of the millennium New Year's Eve celebration in Times Square, he appeared on CNN to warn against melodrama: "When people overdo it about terrorism, terrorists actually win. You're sort of like becoming agents and instruments of the terrorists."

But now Giuliani is running for President, and he has apparently made a tactical decision to thunder loudly about terrorism, perhaps to deflect from his personal life and his liberal record on social issues--which an internal campaign memo termed potentially "insurmountable" last year. (The memo was leaked to the New York Daily News.) The more he can remind people of his performance on 9/11, the better off he is, says GOP pollster Luntz. "You cannot underestimate the impact of having seen him on television hour after hour dealing with the tragedy," he says. "That gives him a level of credibility that nobody else has."

As Giuliani himself put it to the Detroit News recently, "The American people are not going to vote for a weakling. They're going to elect someone who will protect them from terrorism for the next four years." It's the same calculus Bush used in 2004. In fact, it sometimes seems as if Giuliani is in a time warp. Freeh cites this as a point of pride: "If you compare [Giuliani's] remarks to what every politician and most of our citizens were saying on Sept. 12, 2001, you would not find it noteworthy or unusual," he told the Concord, N.H., Monitor.

The question is whether voters have changed. Borrowing rhetoric from one of the least popular Presidents in history may backfire, even for America's mayor. In a recent CBS poll, 46% of respondents said the war in Iraq is actually creating more terrorists. For many, though, the same words sound different when Giuliani says them. Sherie Silverman, 62, went to hear Giuliani in Rockville and left convinced that he "gets it" on terrorism. "He said what I wanted to hear," she said. "I'm looking for a more competent version of Bush." The crowd gave Giuliani a standing ovation.