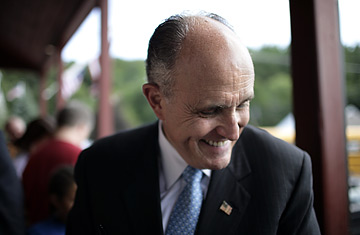

Republican presidential hopeful, former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, visits the Dodge's Store in New Boston, New Hampshire on August 17, 2007.

(2 of 4)

The May session Giuliani missed was a master class on Iraq. He would have gotten briefings from General David Petraeus, the top U.S. commander in Iraq; former Secretary of State Colin Powell; former Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki; and Douglas Feith, the Pentagon's former No. 3 civilian, among others. All told, says a staffer for the Iraq Study Group, "they had 40 of the top experts on Iraq brief them for hours. They had access to anyone they wanted."

After the two no-shows, Baker contacted Giuliani and Alan Simpson, a former Senator who had also missed meetings, to gauge their commitment levels. Simpson affirmed his dedication and was able to make future meetings. But Giuliani formally withdrew, citing "previous time commitments," according to a copy of his letter to Baker provided to TIME by John B. Williams, Baker's policy assistant. Giuliani recently said he resigned because he was considering running for office and it didn't seem right to stay on such an "apolitical" panel. Staffers on the commission say they don't remember that coming up.

Room for Improvement

On the campaign trail, Giuliani's foreign policy comments have sometimes come off more confident than competent. In New Hampshire this spring, according to the New York Times, Giuliani said it was unclear whether Iran or North Korea was further along on building a nuclear bomb. (North Korea tested a nuclear device in October 2006. Iran has not done so.) Then, in his speech at the Maryland synagogue in July, Giuliani mocked Democratic candidate Barack Obama for claiming that North Korea was the nation's No. 1 enemy. "North Korea is an enemy. North Korea is dangerous. I mean, I grant that. And boy, we have to be really careful about North Korea," Giuliani said, his voice iced with sarcasm. "But I don't remember North Koreans coming to America and killing us."

North Korea is known to sell advanced weaponry to other states that sponsor terrorists. The State Department has listed North Korea as a sponsor of terrorism. The reason North Korea keeps U.S. terrorism experts up at night is not that North Korean operatives will come here and attack us; it's that they might sell a nuclear bomb to people who will.

Earlier this summer, the National Intelligence Estimate stated that al-Qaeda has regenerated, directly challenging Giuliani's claims that the war in Iraq has made the U.S. safer. Yet the former mayor continues to insist that the opposite is true: "Being on offense gives us more safety than being weak and being on defense." When I ask him how he reconciles that conclusion with reports that the terrorism threat has increased since we've been "going on offense," Giuliani dismisses those findings and points to the lack of an attack on U.S. soil since 9/11 as evidence of our safety. "Sometimes," he says, "we miss the forest for the trees when we sit in places and just analyze."

In a Foreign Affairs article out this month, Giuliani blames the Clinton Administration's foreign policy for provoking terrorism. "The Terrorists' War on Us was encouraged by unrealistic and inconsistent actions taken in response to terrorist attacks in the past," he writes. He also reaches further back into history, questioning the U.S. decision to leave Vietnam. And his views on Israel sound to the right even of the Bush Administration: "It is not in the interest of the United States, at a time when it is being threatened by Islamist terrorists, to assist in the creation of another state that will support terrorism," he writes.

Democratic Senator Joe Biden is so far the only presidential candidate to directly rebut Giuliani's claim that he knows more about terrorism and foreign policy. "Give me a break," says Biden, who has served on the Senate Foreign Relations committee for 32 years and has been to Iraq seven times. "I'm more qualified than him by a mile." He calls Giuliani a "semidemagogue" on terrorism and criticizes him for mischaracterizing the threat. "I think he gets away with this because the most catastrophic event in modern American history saw him at the base of a building demonstrating some personal courage and taking command." But this is no time for sentimental whimsy, Biden says. "When power is passed from this President to the next, that person is going to be left with virtually no margin for error."

Giuliani can, of course, make up for his experience deficit with his advisers. So far, he has chosen hawkish foreign policy gurus, including Norman Podhoretz, a founding member of the neocon movement who recently called for an immediate attack on Iran, and Kim Holmes, an expert at the Heritage Foundation who advised former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. His chief foreign policy adviser is Charles Hill, a lecturer in international studies at Yale, who says Giuliani doesn't actually require much staffing. "If you run New York City, you know foreign affairs," he says. "In dealing with the U.N. and a host of foreign leaders, that's a host of experiences."

Even if Hill is correct, Giuliani--like all Presidents--would need to be surrounded with the most qualified and competent advisers, particularly when it comes to overseeing homeland security. One of the most damning criticisms of Giuliani, however, has been his record of flawed judgment on personnel. In 2004, Giuliani recommended that President George W. Bush nominate Bernard Kerik to run the Department of Homeland Security. Kerik was a police officer and Giuliani's driver before he was elevated to corrections commissioner and police chief. But the nomination collapsed when information about Kerik's past and possible ties to mob-related businesses began to filter out. Kerik pleaded guilty last summer to improperly accepting $165,000 worth of free renovations on his apartment and may still face federal charges. "I should have done a better job of investigating him, vetting him," Giuliani told reporters this spring. "It's my responsibility, and I've learned from it." (Questions were raised about Giuliani's vetting system yet again in June when his South Carolina campaign chairman, Thomas Ravenel, was indicted on federal cocaine charges.)

For his chief homeland-security adviser on the campaign, Giuliani has chosen Robert Bonner, a partner at the law firm of Gibson, Dunn and a former head of the U.S. Customs Service. But Giuliani's most surprising security adviser so far is his old friend former FBI director Louis Freeh. Freeh's stewardship of the FBI during the eight years before the bureau's most spectacular failure makes him an unusual choice. The 9/11 commission report concluded that Freeh and his FBI had failed to adapt to reality: "Freeh recognized terrorism as a major threat ... [His] efforts did not, however, translate into a significant shift of resources to counterterrorism," the report found. "Freeh did not impose his views on the field offices."