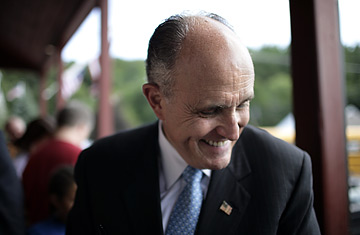

Republican presidential hopeful, former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, visits the Dodge's Store in New Boston, New Hampshire on August 17, 2007.

(3 of 4)

Like Giuliani, Freeh blames President Clinton and Congress for failing to dedicate the necessary resources to the FBI's counterterrorism efforts. "There was no willingness to fund any of this before 9/11," he says. New York City's communication failures on 9/11 should not give voters pause, Freeh says, because today, with new technology and increased counterterrorism funding, things would be different. And then Freeh defaults to the iconic moment, the trump card issued to all Giuliani disciples: "You don't walk through the rubble for one moment on that day and not understand that this cannot happen again and that whatever has to be done will be done."

Following the Sirens

Before 9/11, Giuliani understood what needed to be done in New York City, but getting it done was another matter. In 1994, less than a year into his mayoralty, a depressed computer analyst set off a homemade bomb in a No. 4 subway train as it pulled into a busy station in lower Manhattan. The firebomb, built from a mayonnaise jar, a kitchen timer and batteries, hurt more than 40 people. Passengers spilled, screaming, out of the train, some rolling on the platform to try to put out the flames, others beating back the fire with their coats.

As soon as he learned of the attack, Giuliani did what he always does: he followed the sirens. When he got to the scene, he sought out police, fire and emergency officials. Then he went to the cameras. In an hour and a half, he held 10 interviews. Then he led a press conference in front of two dozen TV crews. "The emergency response," he said, "was close to miraculous."

It was the same public composure in crisis that Giuliani demonstrated to the world seven years later. "Everything is being done to try to make the city as secure as possible," Giuliani said late on the night of 9/11--at his second press conference of the day. "And tomorrow New York is going to be here, and we're going to rebuild, and we're going to be stronger than we were before."

Giuliani's resolve is not just emotionally reassuring. On 9/11, he single-handedly limited the emotional and economic impact of the loss by his measured, confident response. "The fundamental prerequisite is to respond coolly and soberly and not irrationally and emotionally," says Bruce Hoffman, a Georgetown University professor and one of the country's most respected terrorism experts. "I think you could give him credit. Terrorists are trying to provoke us to respond emotionally. He kept his head about him." But that's about the extent of Hoffman's praise. "In Mayor Giuliani's case, it's a very narrow subset of skills where his credentials are unvarnished."

Giuliani dealt with major emergencies on a regular basis. He had time to prepare his city for a major calamity. But did he do all that he could? Much has been made of the fact that Giuliani's state-of-the-art emergency command center was rendered useless on the day of the attacks. The $13 million center was in the World Trade Center complex, on the 23rd floor of Building 7, which collapsed that day. When I asked Giuliani three years after 9/11 if it had been a mistake to place the command center in a known terrorist target, he said no. "You had to put it somewhere," he said. And he noted that the Secret Service and the CIA also had offices in that building. The center was above ground level, leaving it less prone to flood damage (a serious concern in lower Manhattan), and it was within walking distance of City Hall--one of Giuliani's priorities. "In hindsight, it's pretty bad," says John Farmer Jr., senior counsel to the 9/11 commission and the person in charge of reconstructing the response to the attacks for the investigation. "But that's a tough call."

Giuliani's record on managing the city's emergency responders is more telling--and shows a more complicated leadership style than Americans saw on 9/11. "When we reflected on his tenure, we saw qualities that were not helpful," says Jamie Gorelick, a member of the 9/11 commission and former Deputy Attorney General in the Clinton Administration. "[For President], I think you want someone who is not polarizing. Someone who brings people together by the power of persuasion rather than the power of dictate. Someone who is considering of other points of view and ultimately decisive. And on all three scores, I have serious doubts about the mayor."

Remember that 1994 subway firebombing? Despite what he said in public, Giuliani had profound concerns about the emergency response, according to Hauer, who became Giuliani's emergency-management chief in 1996. When Giuliani arrived that day, he couldn't figure out who was in charge. "Rudy walked down there and got one story from the police department, one from fire, one from EMS," says Hauer. "He was very frustrated."

Getting police and fire departments to cooperate is hard anywhere. But New York City was worse than most places. "We had--and still have--a long history of competitive rivalry between the police and fire departments," says Joe Lhota, Giuliani's deputy mayor from 1998 to 2001. This kind of turf war is extremely dangerous. As we now know, the single biggest failing of intelligence agencies before 9/11 and response agencies after Hurricane Katrina was a lack of coordination and communication.

In 1996, to his credit, Giuliani tried to fix the problem. Giuliani established an Office of Emergency Management that reported directly to him. He put Hauer, an experienced emergency manager, in charge. But five years later, the problems persisted. On 9/11 the police and fire departments ran separate command centers, and communication was poor. The firefighters carried the same radios that had failed them in the 1993 bombing. At 10:04 a.m. on 9/11, after Tower Two had collapsed, a member of the New York Police Department's Aviation Unit warned that the top 15 floors of Tower One were "glowing red" and might collapse. Four minutes later, a helicopter pilot said he did not believe the tower would last much longer. Neither of these warnings made it to the fire chiefs. That tower collapsed at 10:28 a.m. "If communications were better," concluded the federal investigation into the collapse, conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, "more firefighters would have been saved."

Before he left in 2000, Hauer tried to get police and fire chiefs to use radios that could communicate with one another. It never happened, partly because of the police department's refusal to cooperate, he says. The mayor could have forced the issue, Hauer says, but he didn't: "Rudy did not back us." On 9/11 the Office of Emergency Management was run by Richard Sheirer, who now works for Giuliani Partners. Giuliani's campaign declined to make Sheirer available for an interview.