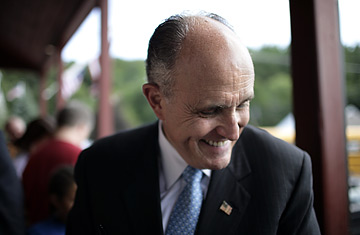

Republican presidential hopeful, former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, visits the Dodge's Store in New Boston, New Hampshire on August 17, 2007.

Islamic terrorists are at war with us," Rudy Giuliani told about 300 people at a synagogue in Rockville, Md., one evening in July. He likes to say it that way--that they are at war with us, not the other way around. "They want to kill us," he warned a group in New Hampshire the same month. "They hate you," he told a woman in Atlanta.

Giuliani says he understands terrorism "better than anyone else running for President," and he certainly talks about it more than anyone else. "Basically, what he's selling is, 'As dangerous a world as this is, I can make it safer,'" says GOP pollster Frank Luntz. So far, it seems to be working. Giuliani has been the consistent front runner of the Republican candidates in most national polls through August.

By framing his campaign this way, Giuliani has raised an interesting question. What does it actually mean to understand terrorism? His supporters might find the question absurd. He owns terrorism, they say. The entire world watched on television as Giuliani led New York City through the aftermath of a terrorism attack. To his opponents, the answer is equally plain: he has no foreign policy experience, and he talks about terrorism as if it's an enemy country on a continent only he knows how to find.

But being a victim of terrorism, or the steely leader of a recovery, is not necessarily the same as understanding terrorism. Nor is foreign policy experience all that matters. So how would Giuliani actually prevent, contain and respond to the next major terrorist attack in the U.S.? What is his vision for what he considers the existential challenge of our time?

This much is indisputable: Giuliani knows what it means to be a victim of terrorism, to lose old friends in an avalanche of violence and spit the dust of a skyscraper out of his mouth in a new, blackened world. He understands the urgency of speaking to the American people after an attack--and not circling above the ruins in Air Force One. He knows how to grieve and go to work at the same time.

But before 9/11, Giuliani spent eight years presiding over a city that was a known terrorist target. A TIME investigation into what he did--and didn't do--to prepare for a major catastrophe is revealing. In addition to extraordinary grace under fire, Giuliani developed an intimate knowledge of emergency management and an affinity for quantifiable results. On 9/11, he earned the trust of most Americans; one year later, 78% of those surveyed by the Marist Institute had a favorable impression of Giuliani. This magazine also named Giuliani its Person of the Year in 2001. Assuming he can keep it, trust is a priceless resource in psychological warfare.

The evidence also shows great, gaping weaknesses. Giuliani's penchant for secrecy, his tendency to value loyalty over merit and his hyperbolic rhetoric are exactly the kinds of instincts that counterterrorism experts say the U.S. can least afford right now.

Giuliani's limitations are in fact remarkably similar to those of another man who has led the nation into a war without end. Some of the Bush Administration's policies, like improved intelligence sharing between countries and our own agencies, have made the U.S. better at fighting terrorism. But others, from the war in Iraq to the treatment of detainees at Guantánamo Bay, have actually made the task much more difficult. The challenge for the next President will be focusing on and adapting the good tools and jettisoning the bad. Whether you conclude Giuliani can win this war depends ultimately on whether you think we are winning now.

A Mayor's Skill Set

Giuliani and his aides said he has been "studying Islamic terrorism" for 30 years. This is an exaggeration. As a prosecutor and Justice Department official in the 1970s and '80s, Giuliani had many successes--against white collar criminals and the Mafia. He did not direct major terrorism prosecutions that led to convictions. As mayor, he worked relatively closely with the FBI, according to James Kallstrom, former FBI assistant director in charge of the New York office. "The four years that I was there, we had a fabulous relationship," says Kallstrom. "He was able to do many things in this city that I never expected him to be able to do."

But until 9/11, the security obsession of Giuliani and the FBI was crime, not terrorism. He came into office 11 months after the first attack by Muslim extremists on the World Trade Center. Yet an analysis of 80 of Giuliani's major speeches from 1993 to 2001 shows that he mentioned the danger of terrorism only once, in a brief reference to emergency preparedness. He talked more about the "terror" of domestic violence.

With his own preparedness staff, he did discuss terrorism, says Jerome Hauer, Giuliani's emergency-management chief from 1996 to 2000. Giuliani was certainly more aware of the subject than most mayors, which made sense, given the city's panoply of targets. But he was not a student of Islamic extremism, as he claims on the campaign trail, Hauer says. (Giuliani and Hauer had a falling-out during the election to replace Giuliani after 9/11, both sides confirm, after Hauer endorsed a Democrat, arguing in part that the city would be safer under his choice.) "We never talked about Islamic terrorism," Hauer says. "We talked about chemical terrorism, biological terrorism. We did talk about car bombs every now and then. [But] I don't think there was much interest on his part. If he's been studying it for 30 years, he certainly never verbalized it to me."

Giuliani has also claimed he knows more about foreign policy than other candidates, but that's exceedingly unlikely. John McCain spent 22 years as a Navy pilot and five as a prisoner of war and is now the ranking member of the Armed Services Committee in the Senate, where he has served for 20 years. He has been to Iraq six times; Giuliani has never been there. (Of the major candidates, only Giuliani, Fred Thompson and John Edwards have never visited Iraq.)

Giuliani had an unusual opportunity to cram foreign policy when he was invited to join the Iraq Study Group by the co-chairman, former Secretary of State James Baker III, in February 2006. Giuliani accepted, becoming one of just 10 people, including former Secretary of Defense William J. Perry and retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, in the congressionally mandated group. He participated in a conference call to discuss logistics but then did not attend the first two major meetings. On those days, he delivered paid speeches.