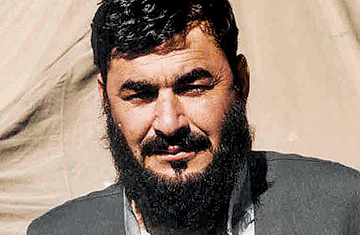

Bashir Noorzai, an Afghan who is on the United States' list of most wanted drug kingpins.

(8 of 8)

Now, in the Taliban's traditional stronghold in the south--where Noorzai's tribe lives--the radical Islamic group is actively encouraging poppy cultivation on a grand scale, a dramatic shift from its days in power when its puritanical tenets forbade drugs and drug trafficking. Why the change? As a Western diplomat in Kabul puts it, "It takes money to fund an insurgency." Of the $3 billion earned last year by Afghan narcotraffickers, roughly $800 million trickles down to the Afghan farmers who grow the crop. According to a senior Western official in Kabul, a small portion of that sum is "more than enough to finance" the insurgency--and the Taliban gets more than a small portion. "The more money the traffickers make, the more they can give to the Taliban, the more weapons the insurgents can buy and the more dangerous the insurgency becomes," says Kamal Sadaat, head of Afghanistan's antinarcotics police force.

"God willing, I look forward to my trial," Noorzai says in detention in New York City. He will have a lawyer with an imposing 6-ft. 5-in. frame and a high-profile list of legal contests, if not victories. Ivan Fisher made his name defending Jack Henry Abbott, a convicted killer whose gritty prison memoir, In the Belly of the Beast, was famously championed by Norman Mailer. Fisher is no stranger to bad guys. In the 1990s, Fisher defended Haji Ayub Afridi, a man widely believed to be one of Pakistan's major narcotraffickers, as well as someone who was thought to have worked closely with the CIA during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Afridi served 3 1/2 years for drug trafficking, a verdict that at the time was considered a defeat for the prosecution. Fisher does not apologize for his current client. This case, he asserts, "is about the [Bush Administration's] incompetence in waging the war on terror in Afghanistan. Haji Bashar Noorzai wanted to be an ally, not an enemy."

The prosecution remains silent about its plans, but sources say the government will insist on the importance of the Noorzai catch. He is, says a Western official with detailed knowledge of the case, the "Pablo Escobar of Afghanistan"--a reference to the notorious druglord of Colombia. Fisher says his client won't cop a plea, even though the documents TIME has seen indicate he might be able to implicate major figures in Afghanistan. A former DEA official counsels patience in the quest for justice: "It's a long, hard slog. You've got to give it years. We were starting from the ground up here."

The trial can be seen as a test case for the costs and benefits of arresting and prosecuting a man like Noorzai. Does the potential cost to the battle against terrorism in Afghanistan outweigh the benefit to the war on drugs? These are the kind of wrenching questions that the U.S. must weigh in its new twilight struggle for stability both at home and abroad.

For his part, Noorzai insists that his offer to help stabilize Afghanistan was sincere. He is also certain that he offered his help to the right people: "I still believe American and NATO forces are the only ones who can help Afghanistan rebuild." They will just have to do it without him.