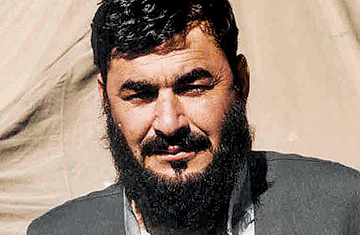

Bashir Noorzai, an Afghan who is on the United States' list of most wanted drug kingpins.

(4 of 8)

Noorzai's position as tribal leader was more than an honorific. Leadership is not simply inherited: while descent is important, a chief usually emerges by consensus, recognized for his military prowess, his charisma, and his skill with money and negotiation. Noorzai needed all those qualities when the world changed on Sept. 11, 2001. He immediately understood that the U.S. would retaliate and that the Taliban's days were numbered. That day Noorzai was at one of his homes in the Pakistani border city of Quetta, a two-story fortresslike structure. He left quickly for Afghanistan to prepare for the coming trouble and then returned to Pakistan just before the U.S. assault began. He was not wrong to sense personal risk: his closeness to Mullah Omar led to Noorzai's designation as a "high-value military target" by the U.S.

A month after the U.S. invasion, Noorzai sent word via one of his relatives, a man named Khalid Pashtoon, to say he wanted to meet with the U.S. military. It is a testament to either craftiness or desperation that Noorzai turned to Pashtoon, who despite the family tie was a key aide to a rival tribal chief who often clashed with Noorzai. But that enemy was one of America's chief allies in the south of the country. The seeming alliance did the trick. In November 2001, instead of being targeted, Noorzai was meeting with the Americans.

Noorzai has a flair for the dramatic gesture. In January 2002, to convince the Americans that he wanted to work with them and demonstrate not only his worth but his influence over his tribe, he delivered 15 trucks loaded with weaponry, including about 400 antiaircraft missiles, that the Taliban had concealed in his tribal villages. The gesture apparently had the desired effect. Over the next few months, Noorzai said he met with U.S. military and intelligence officers five times. The purpose, he says: "To make the situation in Afghanistan stable and also to help the Americans negotiate with the moderate members of the Taliban to reconcile with the [new] government."

Toward that end, Noorzai says, he played a critical role in delivering up the Taliban Foreign Minister, who had fled, like much of the leadership, to Quetta following the invasion. In February 2002, Mullah Wakil Ahmad Muttawakil's surrender made headlines around the world. Noorzai says he had invited his childhood friend to talk to the Americans, believing him to be the sort of "moderate" that Washington was seeking to work with. Noorzai says, however, that this would lead to his first betrayal by the Americans. Instead of incorporating his friend into the Afghan government, the Americans took Muttawakil to the U.S.-run prison at Guantánamo Bay. He would not be freed for 21 months. Noorzai was furious.

A second and similar incident followed a few months later. Noorzai says he had persuaded a former mujahedin fighter named Haji Birqet Khan, 75, who was close to the Taliban, to come out of hiding in Pakistan and meet with the Americans. But days after Birqet and Noorzai got together in Kandahar, U.S. attack helicopters swooped in and bombarded Birqet's home, killing him and two of his grandchildren. The U.S. claimed it had got wind of a plot by Noorzai and Birqet to attack American forces. Noorzai says that report was erroneous. "He was an innocent man, a tribal leader who had come back to help," Noorzai says.