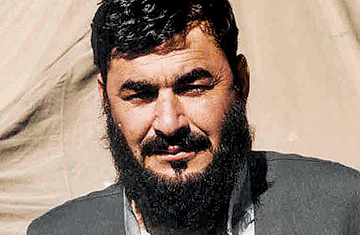

Bashir Noorzai, an Afghan who is on the United States' list of most wanted drug kingpins.

(2 of 8)

Unlike Iraq, Afghanistan is a war fought backward, not a massive invasion on the front end but a minimalist effort that now demands a massive rescue operation. The situation in Afghanistan, a larger country with a bigger population than Iraq's, is so serious that the number of U.S. forces in the country has jumped more than 50% in the past year, to 27,000, a much bigger surge in percentage terms than is being argued over for Iraq. There are six times the number of soldiers as in 2002 when U.S. forces were staking out bin Laden in Tora Bora. Only now the enemy is not just the Taliban and al-Qaeda but also the proxy army of warlords that the U.S. helped enrich and empower--an army that America once hoped would be critical in the struggle against terrorism.

It is in this context that U.S. officials argue over who's a friend, who's an enemy and how you can tell them apart. Drug enforcement officials claim Noorzai's capture as a major prize. Afghanistan is the world's largest source of heroin, and his arrest, says DEA administrator Karen Tandy, "sent shock waves through other Taliban-connected traffickers." But Noorzai was also a powerful leader of a million-member tribe who had offered to help bring stability to a region that is spinning out of control. Because he is in a jail cell, he is not feeding the U.S. and the Afghan governments information; he is not cajoling his tribe to abandon the Taliban and pursue political reconciliation; he is not reaching out to his remaining contacts in the Taliban to push them to cease their struggle. And he is hardly in a position to help persuade his followers to abandon opium production, when the amount of land devoted to growing poppies has risen 60%.

Valuable intelligence assets are seldom paragons, and the best are valuable precisely because they have traveled down the darker alleys and know where opportunities and danger lie. However unsavory the résumé, says Alexis Debat, senior fellow at the Nixon Center and an expert in counterterrorism in South Asia, "it is always a smarter move to leave someone in place as long as you are getting reliable information." Noorzai's story is both a symbol and an example of this critical debate over means and ends. In addition to speaking to Noorzai exclusively in a two-hour phone interview granted after a court hearing, TIME has reviewed hundreds of pages of transcripts of secret meetings between him and U.S. government agents. They reveal an extraordinary saga of intrigue, espionage and, from Noorzai's perspective, betrayal. Awaiting trial in New York City, Noorzai says the U.S. and NATO forces occupying Afghanistan have made "a lot of errors." His arrest, he asserts, "was one of them."

The Devolution of Afghanistan into druglord-run provinces is a direct, if unintentional, result of five years of U.S. management of the Afghan war. When the U.S. invaded in October 2001, it was with a small number of mostly special-forces soldiers; the strategy all but ensured that the U.S. would have to outsource the messy and labor-intensive duties of maintaining order in a power vacuum. This meant using, and paying, the existing warlords to do the U.S.'s dirty work against Mullah Omar's Taliban and bin Laden's al-Qaeda.