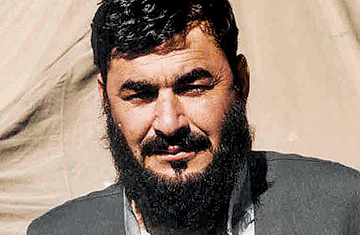

Bashir Noorzai, an Afghan who is on the United States' list of most wanted drug kingpins.

(3 of 8)

Notwithstanding the fact that both men escaped, the plan appeared to work well enough at first. The U.S. never needed to increase the number of forces serving; instead it just paid off and armed the warlords. This temporarily slowed the opium traffic, since the U.S. payroll was more efficient, less risky and paid in hard currency. But when the flow of money slowed and the warlords returned to opium cultivation as the U.S. turned its attention toward Iraq, whole provinces were back in the drug business and officials in Washington began to be worried the Taliban would reap the benefit. If it were a sovereign state, just the southern province of Helmand--a Taliban stronghold--would be the second largest source of opium in the world. The rest of Afghanistan would be the first. "The drug trade," Debat observes, "is the blood of the insurgency in Afghanistan."

Today opium cultivation in Afghanistan is a growth industry. What crude oil is to the Middle East, poppies are to Afghanistan. A senior Afghan official estimates that 30% of the country's farmers now grow poppies, while the U.N. estimates that the area under cultivation increased 59% in the past year. Experts suggest that the drug situation in Afghanistan is moving from one that was manageable to one that is verging on being out of control.

One of the beneficiaries of that growth industry, according to the DEA, is Noorzai. He inherited not only his land but also his trade from his father. Several sources in Afghanistan claim that Noorzai's father was a successful drug smuggler. "This was definitely the family business," a Western official says. The tribal chief's family had had its vicissitudes: the communists who ruled Afghanistan till 1989 had stripped them of their land, and the teenage Noorzai went off to fight alongside the mujahedin in their war against the occupying Soviet forces. After the Soviets left, Noorzai made several thousand dollars recovering Stinger missiles at the behest of U.S. agents. After the war, Noorzai allegedly returned to the family trade. By 1993 the DEA was describing Noorzai as a "wealthy heroin warlord and well-known drug trafficker."

When the Taliban came to power in 1996, according to the DEA, Noorzai reached the peak of his influence. While Taliban leader Mullah Omar's tribal background is not known, he was always reliably supported by the Noorzai tribe. Even when the ruling Taliban was cracking down on the opium trade, Noorzai's closeness to the regime allowed Noorzai to become one of just four big traffickers permitted to grow and process poppies, according to Jamil Karzai, a current member of the Afghan parliament and a second cousin of President Hamid Karzai's. In 1997, the DEA says, Noorzai's organization had successfully shipped 57 kilos of heroin, most likely through Pakistan and then Eastern Europe, to the streets of New York City. Noorzai denies all charges.