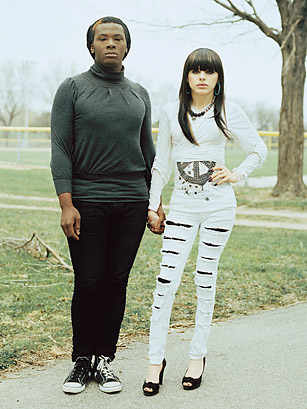

Jayde LaPorte, right, a transgender ninth-grader, and Robbie Moore attend Milwaukee's Alliance School.

(3 of 3)

The other source of opposition was the gay community itself. "We had the most resistance from within the LGBT community," says principal Chad Weiden, who ended up rescinding the proposal. The project's gay critics, some of whom referred to it as Homo High, suggested that such a school would not only create the impression that intolerance would be permitted everywhere else but also leave its sheltered graduates unprepared to deal with the sometimes harsh realities of being a gay person in America. "I believe ultimately the only real answer is integration," says Savin-Williams, the Cornell professor who for more than two decades has studied the experiences of gay youth. "We need to provide normal educational experiences for these kids. They see themselves as a part of mainstream society and really want to be a part of it all."

That's why many school districts, instead of opening separate gay-friendly schools, are trying to build acceptance of LGBT students from within. San Francisco Unified School District, for example, has placed a full-time liaison at each middle and high school to educate everyone about the effects of harassment and help manage clubs designed to promote students' acceptance of one another. "We're sending a message that we respect all students in our schools," says Kevin Gogin, manager of the citywide program, which has been in place since 1991.

Other districts have chosen to use kits from GLSEN that provide "Safe Space" stickers and posters as well as a guide on how to build a support network for LGBT students. Since GLSEN started its awareness campaign last November, 15,000 Safe Space kits have been distributed nationwide; the state of Idaho recently ordered one for each of its high schools. There has also been an uptick in the number of GSAs, from a single club in Massachusetts in 1998 to more than 4,000 clubs nationwide. According to GLSEN's 2009 survey, LGBT students in schools with a GSA club were less likely to feel unsafe because of their sexual orientation and heard fewer homophobic remarks than their peers at schools without such a club.

Though GSAs and other efforts work to promote a climate of respect, progress is often slow, and advocates for schools like Alliance say there is no reason LGBT students should be forced to endure hardship until society gets to the point where all schools are safe for all students. "Acceptance is not happening fast enough," says Weiden. "We need to help these kids by providing them a better option, a safe space, right now."

Meanwhile, Owen fields calls nearly every day from parents and administrators at Milwaukee-area schools about students who would like to transfer to Alliance, whose charter is likely to be renewed in the spring without much of a fight. She also gets calls from teachers across the country seeking advice on how to decrease bullying. She is happy to dispense some tips but makes clear that not even Alliance has managed to eradicate such behavior. A few weeks ago, one of its ninth-graders created an "I hate so-and-so" Facebook page about another kid at Alliance. But students didn't stand idly by. They alerted Owen within minutes of the page's existence, and she quickly got the boy to take it down. The following week, a group of students met to discuss an appropriate punishment. They decided to have the ninth-grader apologize directly to the student he had targeted and also to the entire student body over the school's intercom system.

Dylan Huegerich followed the fracas on Facebook, but he's no longer attending Alliance; the 90-minute commute was just too long. He didn't feel ready to face the bullies at his local school, so his mother opted to enroll him in an online academy. That doesn't mean, however, that he's holed up alone at home. He recently attended a homecoming dance at his boyfriend's school, and though people said nasty things as the two boys made their way inside, Dylan notes, somewhat optimistically, that the trash talkers were parents rather than students. He adds, "It seems like my generation is getting over it."