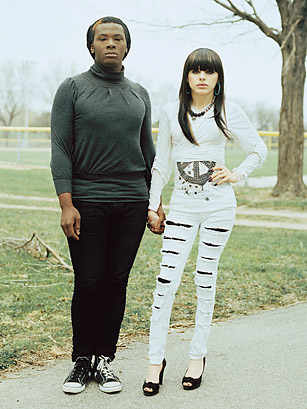

Jayde LaPorte, right, a transgender ninth-grader, and Robbie Moore attend Milwaukee's Alliance School.

(2 of 3)

At Alliance, it's a different story. Founded in 2005, the high school expanded to include middle schoolers in 2009, and its students have somehow managed to create an environment in which everyone's sexuality is on the table and yet at the same time is almost a nonissue. After "What's your name?" and "Where are you from?" often the next getting-to-know-you question is "Are you gay or straight?" For many kids, the answer is "I don't know yet," and that's fine too.

Jayde LaPorte might as well be the school's mascot. A transgender ninth-grader who was born as a boy named Luis, she walks Alliance's halls in three-inch heels, with long, salon-perfect hair (it's a wig) and silver earrings so huge, they almost touch her shoulders. It's hard for her to get anywhere quickly because she pauses every few steps to give someone a hug. As a young boy tromping around the house in heels and a balloon-stuffed bra, Jayde was so confused and upset that she remembers thinking about suicide at age 6 or 7. When she arrived at Alliance in seventh grade, she met Robbie Moore, who is now in 11th grade and whom Jayde calls her "tranny sister." He helped Jayde learn how to do her makeup and hair and walk in heels. "Robbie is filling a space in my heart," Jayde says, tears welling up in the corners of her eyes. "He's teaching me everything I need."

That kind of support is the goal at Alliance. Instead of being tormented, Jayde and Robbie can walk tall, in heels or whatever else they feel like wearing. "I always felt these kids could survive in other places, but they could thrive here," says Alliance's founder and lead teacher, Tina Owen. She decided to start the school after she was outed at a large Milwaukee high school where she worked as an English teacher. After word spread, she decided her sexuality may as well be all the way out. She hung rainbow curtains in her classroom and painted the radiators in rainbow colors. "I wanted kids to know they were O.K., that there was a safe space here," she says. But even though she was running a Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) club after school, she heard stories of students being assaulted in the hallways and called gay slurs. She noticed some kids were skipping school more often and then would stop showing up at all. "They were trying to be strong and carry the load, but they were dropping right before my eyes," she says.

Owen decided to try to replicate the GSA atmosphere on a round-the-clock, campuswide basis. Her model was New York City's Harvey Milk High School, which opened in September 2003 and serves about 100 students each year. Harvey Milk is an offshoot of an after-school program started by the Hetrick-Martin Institute that since 1985 has been providing health and counseling services, tutoring, college prep and elective courses to LGBT students. Another charter school, which opened last year on the grounds of the Los Angeles Gay & Lesbian Center, offers independent study — rather than regular classes — to students in grades 7 through 12. Like Alliance, these schools carefully word their mission statements to avoid even the slightest whiff of bias against nongays. New York was once sued amid demands to revoke funding for the Harvey Milk School on the grounds that it violated the city's antidiscrimination laws. The suit was eventually settled when the school made it clear that it is designed for but not limited to LGBT students.

De Facto Segregation

Each of these schools is forced to walk a fine line in creating a safe space that is welcoming to LGBT students without alienating or excluding others. That was precisely the challenge a group of staff members and students at Chicago's High School for Social Justice encountered in 2008 when they tried to open a gay-friendly school in the Windy City. Though the proposal was welcomed in community forums and given a green light by then superintendent Arne Duncan, who a few months later was named Secretary of Education by President Obama, two distinct opposition groups came forward. The first was a group of ministers who argued that since gay teens are not the only ones being bullied, taxpayer dollars should not be used to provide a special school for them. "It's not fair," the Rev. Wilfredo De Jesus, an Evangelical minister, told the Chicago Journal.