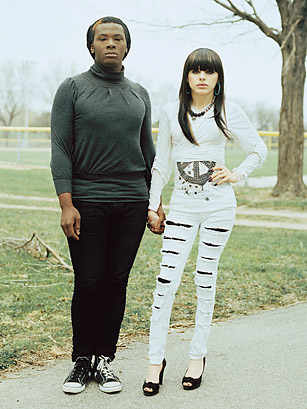

Jayde LaPorte, right, a transgender ninth-grader, and Robbie Moore attend Milwaukee's Alliance School.

The taunting started four years ago, when Dylan Huegerich was 10. Back then, he didn't know what being gay meant, and even today the soft-spoken teenager isn't sure where he fits on the spectrum of sexual orientation. He knows he's different. He knows that his sense of style — his chin-length hair, his dabbling with makeup — caught the eyes of school bullies in Saukville, Wis. In seventh grade he was pelted with snowballs and shoved into lockers. Everywhere he went on campus, students shouted anti-gay slurs and pointed and stared. "It hurt so bad," he says. "I hated my life. I hated everything."

His mother Amy tried to intervene. She says she was told it was her son's fault for standing out and that he should cut his hair or try to act "more manly," allegations the principal declined to comment on. Dylan's mother considered volunteering in his classroom or the cafeteria, but that wouldn't protect him the rest of the time. Every morning, she says, "I knew I was driving him back to this place where he was hurting. Oh, they beat you up? Here, go there again. My heart broke every time he got out of the car." When the time came to register Dylan for eighth grade, she decided against re-enrollment. "I felt like if I turned in those forms, I was giving him some kind of a sentence," she says.

So instead of sending Dylan back to a school that was a 10-minute drive from his house, his mother opted for the publicly funded Alliance School, an hour and a half away in downtown Milwaukee. The only overtly gay-friendly charter school in the U.S. to accept students as early as the sixth grade, Alliance has several boys who, with their painted nails and longer hairstyles, look like Dylan. But more important, it has many students who say they know how Dylan feels. While only about half of Alliance's 165-member student body identifies as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT), nearly all were bullied or harassed at their previous schools. The hallways are filled with masculine girls, effeminate boys, punks, goths, runts, the overweight and the ultra-nerds. Alliance art teacher Jill Engel affectionately calls the school "the island of misfit toys."

The Alliance School is a radical solution to a much debated problem. Children have long been taunted with homophobic slurs, but a recent string of high-profile suicides has led school and government officials to pay more attention to this subset of bullying victims. Nine out of 10 LGBT students say they have experienced bullying or harassment, according to a nationwide survey of 7,261 middle and high school students conducted in 2009 by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). Nearly two-thirds of respondents said they have felt unsafe in school; 1 in 5 reported having been physically assaulted.

Parents want to protect their kids, but is wrapping them in an Alliance-style cocoon of tolerance the best solution? Some conservatives oppose the idea of a gay-friendly school on moral grounds, others for fiscal reasons: Why should taxpayers help make sexuality a central part of a child's or a school's identity? Developmental experts — and many gay activists — question the wisdom of shielding some students rather than teaching kids coping skills and promoting an atmosphere of respect on all campuses. "Being segregated doesn't help gay kids learn, it doesn't help straight kids learn, it doesn't help bullies learn," says Ritch Savin-Williams, a professor at Cornell University who chairs the human-development department. "All it does is relieve the school and the teachers of responsibility. It's a lose-lose situation all around." And yet to some bullying victims, it's nothing short of a lifeline.

A Place to Walk Tall

It wasn't all that long ago that people didn't contemplate coming out at school until college. In 1974, students at Rutgers University began a tradition called Gay Jeans Day, during which heterosexuals could show their solidarity with gays by wearing jeans to class. This setup meant that homophobes — as well as libertarians and anyone else who didn't like being forced to make a statement — had to choose whether to draw attention to themselves by wearing something else. But as people have started coming out at younger ages, many middle and high schools have become staging grounds for more-involved demonstrations, such as the Day of Silence in April, when participants refuse to speak even in class in order to raise awareness of what many gays say is a forced silence, and National Coming Out Day on Oct. 11. That date was chosen to commemorate a gay-rights march in Washington in 1987, but the timing can be tough, particularly for younger students, forcing a high-pressure will-they-or-won't-they moment on them less than two months into the school year.