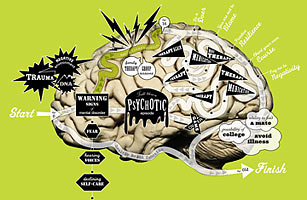

We tend to view the brain like an alien that happens to reside in the skull. We see it as unpredictable, ungovernable in ways that other organs aren't. Proper diet, exercise, no smoking — these will help prevent heart and lung disease. But diseases of the mind? They strike at will, right? You just can't keep yourself from going crazy.

And yet — what if you can? The most exciting research in mental health today involves not how to treat mental illness but how to prevent it in the first place. Hundreds of studies that have appeared in just the past decade collectively suggest that the brain isn't so different from, say, the arm: it doesn't simply break on its own. In fact, many mental illnesses — even those like schizophrenia that have demonstrable genetic origins — can be stopped or at least contained before they start.

This isn't wishful thinking but hard science. Earlier this year, the National Academies — an organization of experts who investigate science for the Federal Government — released a 500-page report, nearly two years in the making, on how to prevent mental, emotional and behavioral disorders. The report concludes that pre-empting such disorders requires two kinds of interventions: first, because genes play so important a role in mental illness, we need to ensure that close relatives (particularly children) of those with mental disorders have access to rigorous screening programs. Second, we must offer treatment to people who have already shown symptoms of illness (say, a tendency to brood and see the world without optimism) but don't meet the diagnostic criteria for a full-scale mental illness (in this case, depression).

Neither approach is without controversy. Early-detection programs will identify as candidates for mental illness some people who are merely persnickety or shy or eccentric. Some prevention programs even prescribe psychiatric medications, including antipsychotics and antidepressants, to people who aren't technically psychotic or depressed. "This is a big concern," says Joseph Rogers, founder of the Philadelphia-based National Mental Health Consumers' Self-Help Clearinghouse. "Because, gee, if you miss, you can really do more harm with some of these drugs than good."

But those who contributed to the National Academies report say preventing the suffering of people with mental illness is worth the risk of some false positives, partly because of the enormous cost of treating mental illness after it's struck. The National Academies estimates that the total economic cost of mental disorders just among Americans under 25 was $247 billion in 2007. (There are no such recent figures for all adults, but one 2000 study estimated that in 1992, the total cost of adult mental illness was $161 billion.) Another 2007 study found that more than a quarter of the costs for young people are incurred in the education and juvenile-justice systems, which must deal with illnesses that, in many cases, could have been prevented.

But how do you predict and stop disorders as capricious and varied as depression and schizophrenia? Though treatment of mental illness is far more costly over time, prevention isn't without up-front costs. In a health-care system already overburdened, who pays? More fundamentally, what kind of country will we have if we attempt to "cure" various odd behaviors and quirky traits — qualities that can sometimes look like symptoms of a coming illness and other times look like evidence of a lively mind?

Prevention Pioneer

In the early 1970s, before Dr. William McFarlane was one of the world's top authorities on preventing mental illness, before his hair had thinned and receded to a salt-and-pepper pouf, back when he was a student at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, few psychiatrists talked about prevention. At the time, the U.S. had half a million psychiatric beds (there are 200,000 today), and psychiatrists faced less financial pressure to move inpatients quickly to outpatient care. Many people spent years on locked wards, their brains slowly gelatinizing from the combination of underlying illness and the blunt-instrument antipsychotic drugs of the day.

After he finished school and began seeing patients and teaching, McFarlane, like a few other pioneers, started to wonder if you could do something to stop the cycle before it began. But there was little research at the time on the early stages of mental illness. A key break came in the late 1970s, when a UCLA team began to publish the results of an influential long-term study called the UCLA Family Project. The study found that you could predict, with remarkable accuracy, which 16-year-olds would develop schizophrenia later in life based on only a few characteristics. The teenagers whom the Family Project tracked had already sought treatment for a psychological problem, although the study excluded actively psychotic teens, since it would not have been a surprise if they had developed schizophrenia.