(3 of 4)

How long is the window between first symptoms and actual diagnosis? The National Academies report says that across several mental illnesses — including obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression and substance dependence — we have about two to three years to intervene and keep short-term symptoms from becoming long-term afflictions.

Depression offers particularly good evidence of this idea at work. Currently, about 5% of adolescents experience an episode of clinical depression in any given year. Rates of depression are three to four times as high among the children of depressed parents as among those whose parents aren't depressed. Dr. William Beardslee of Children's Hospital Boston, one of the authors of the National Academies report, has spent more than 25 years studying how some kids of depressed parents avoid the illness, and he has found that resilience is key. The kids who don't develop depression are "activists and doers," Beardslee says. Even growing up in the darkness of a depressed home, they muster the capacity to engage deeply in relationships. They also are likelier than other kids to understand that they aren't to blame for their parents' disorder — and that they are free to chart their own course.

How do you foster resilience in order to prevent depression? Over the past 17 years, Beardslee's team has developed an early intervention that targets kids from families in which at least one parent is depressed. Like McFarlane, he uses a family-based approach because a bad home environment tends to be more predictive of adolescent mental illness than dysfunctional peer relationships are. Beardslee's Family Talk Intervention includes both separate meetings with parents and kids as well as family meetings with social workers or psychologists that focus in part on demystifying depression — explaining that it is a treatable illness, not a beast that will necessarily crush a family. In a randomized trial, Beardslee found that just seven sessions of this intervention decreased predepression symptoms among the kids and improved the parents' behavior and attitudes. All this makes kids more resilient.

Tackling Schizophrenia

McFarlane hadn't gotten far with the New York City schools in the 1980s, and his prevention work waned for a few years as he taught at Columbia University and wrote articles on his Multi-Family Group approach to treating psychosis. Eventually, he moved to Portland, Maine, where he had been offered the chairmanship of Maine Medical Center's psychiatry department. There, he settled into quieter, less paradigm-changing work.

It wasn't until 1996 that his prevention work resumed. That year, a team of researchers in Norway — one that included Dr. Thomas McGlashan of Yale — approached McFarlane about training therapists to use the Multi-Family Group approach with patients who had just suffered a first psychotic episode. These patients already had the illness, so it was too late for prevention. But the Norwegians had succeeded where McFarlane had failed in New York: they had connected with schools and other local institutions to identify the first signs of psychosis and refer patients to the team immediately.

In October 1998, the picture grew still more promising when NATO sponsored a major psychotic-disorders conference in Prague, where McFarlane learned that several groups around the world, including one in Australia, had also been trying to prevent first episodes of psychosis. He returned from Prague and tried again to set up an early-detection system with schools, this time in Portland. By now, the stigma against mental illness had eased a bit; schools had seen a dramatic rise in emotional and behavioral problems during the '90s. Unlike their New York counterparts, Portland school superintendents welcomed McFarlane.

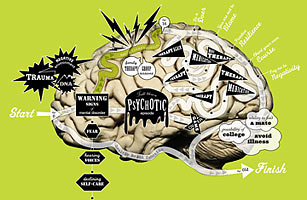

At about the same time, McGlashan's team at Yale was working on a screening interview that might distinguish kids who would become psychotic from those who wouldn't. McGlashan tested his questions at various sites in North America, including with teens who sought treatment in McFarlane's department in Portland. By 2001, McGlashan and his team had completed their "Structured Interview for Prodromal [pre-disease] Symptoms" (SIPS) — a two-hour assessment involving various oral tests and a family history. Those who meet SIPS criteria for risk are about 30 times as likely as the general population to develop a diagnosable psychotic disorder. SIPS allows for the careful scoring of warning signs, some of which are obvious (hearing mumbling that isn't there) and some of which are less so (changing your behavior because of a superstition).

McFarlane and his team connected with most of Portland's principals and pediatricians. The message was simple: If you encounter kids who seem slightly off — prone to jumbled thoughts, maybe even hearing voices — send them our way. Among those referred to him, McFarlane found that 80% of those who met SIPS criteria for prodromal psychosis would receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia within 30 months. He put kids who met a certain SIPS threshold into Multi-Family Group psychoeducation. At first, he intended not to use drugs with these prediagnosis kids, particularly since the meds can cause side effects like weight gain, acne and uncontrollably shaky legs. But McFarlane found that once symptoms like auditory hallucinations started, he couldn't correct them with only psychosocial interventions. (Today, virtually everyone enrolled in his Portland Identification and Early Referral prevention program is prescribed psychiatric medication.)