(5 of 5)

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

Breakthrough drugs are hard to plan for, and if you're trying to get your appetite under control today, they do you no good at all. But other studies in the appetite field could produce results sooner. At the Pennington Center in Baton Rouge, investigators run what may be the most sophisticated metabolic test kitchen in the country, hoping, in part, to determine which kinds of meals satisfy us best with the smallest penalty to pay on the scale. The kitchen looks like any other, with the exception of the laboratory instruments that allow investigators to determine the metabolic impact of eating, say, 90 grams of a pancake breakfast as opposed to 113 or 123. People battling weight problems volunteer for several-day stays to test the menus and undergo other studies in order to help both themselves and others.

At the moment, some of the research in the kitchen involves trying to find a more precise way to balance the glucose loads various foods deliver to the body. That's important, since the bigger the glucose hit, the greater the sense of satiation, but only for a little while. Afterward, hunger returns stronger than ever. "High glycemic foods like refined breads and sugars push the body to refuel," says nutrition scientist Marlene Most, head of the metabolic kitchen. "In low glycemic foods, there is a constant flow of glucose and insulin, so we don't need to refuel as much."

Pennington neuroscientist Christopher Morrison has looked at another, comparatively fast-track approach to appetite control. If leptin supplements have been such a disappointment in keeping food intake in check, what about leptin combined with other natural suppressants such as CCK? In animal studies conducted in a lab where Morrison did his postdoctoral work, doses of CCK followed by leptin did a better job of curbing appetite than either one alone. "There have been some good data to suggest that the [effectiveness] of short-term CCK signals are influenced by the presence of leptin," Morrison says.

Other, still more direct strategies rely on other, still simpler mechanisms. Most people on diets notice that their hunger pangs seem to diminish over time. Perhaps they're just getting used to living with their cravings, but the recent findings showing that leptin may become more effective as obese people shed fat suggests a biochemical mechanism is at work. While knowing this won't make the weight fall off faster, it does provide one more incentive to stay the dietary course.

Barbara Rolls, a professor of nutritional sciences at Pennsylvania State University, advocates another way to attack hunger even more aggressively. Rolls currently tops the best-seller lists with a book about what she calls the "volumetrics" eating plan—the kind of prefab word that cries out diet fad but in this case describes a sensible idea, provided that it's followed in moderation. The key to volumetrics, Rolls explains, is to consume foods that are high in volume but not in calories in order to stimulate the digestive system's distension nerves. It's the difference between, say, a large, filling salad with a low-calorie load and a small, unfilling brownie with a high one.

"This whole idea of eating smaller portions—I'm really fed up with it," Rolls says. "It's not big portions that make you eat more. It's big portions of calories. If you eat big portions of fruits and vegetables, they displace other foods." Rolls stresses that it's important to eat a variety of tastes and textures. If you overload on one thing—say, the heavy dose of meats that the low-carbohydrate Atkins plan recommends—you're going to crave the sweet or crunchy or doughy experience of the fruits and breads you're forbidden. "It's called sensory-specific satiety," she says, and it's one of the reasons we still have the appetite for a sweet dessert even after we stuff ourselves with a heavy dinner.

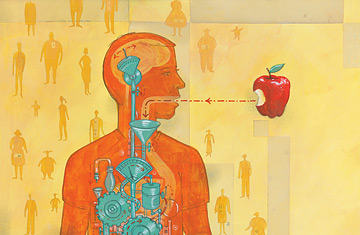

The very discordance between a mouthful term like sensory-specific satiety and the uncomplicated joy of a crème brûlée at the end of a meal speaks to the puzzle that is the human appetite. We may always be pleasure-seeking creatures, intoxicated by the very experience of food—with its colors and textures and notes of flavor—but that doesn't mean our ancient impulse to eat whenever we can must always yield to our modern ability to satisfy that urge. The same human brain that invented the food court and the supermarket must now develop ways to control how we use them. Just as when we were learning to eat on the savanna, our health and even survival may be at stake.

—Reported by Dan Cray/Los Angeles, Elisabeth Salemme/New York and Carolyn Sayre/Baton Rouge