(3 of 5)

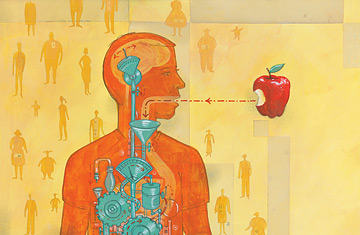

THE HUNGER HORMONE

Identified in 1999, ghrelin is often called the hunger hormone because that precisely captures what it does. Ghrelin is produced in the gut in response to meal schedules—and, according to some theories, the mere sight or smell of food—and is designed to give rise to the empty feeling we recognize as wanting to eat. When ghrelin hits the brain, it heads straight for three areas: the hindbrain, which controls the body's automatic, unconscious processes; the hypothalamus, which governs metabolism; and the mesolimbic reward center in the midbrain, where feelings of pleasure and satisfaction are processed. That's a neural triple play that guarantees that when ghrelin talks, the brain will listen.

Cummings has conducted studies in which he measured the hormone in people's blood every 20 min. and found that levels reliably spike as mealtimes approach. Add or subtract a daily meal, and you soon gain or lose a surge. "Grazing animals have little spikes of ghrelin all day long—20 to 30 in the case of a rat," Cummings says. One of the reasons gastric-bypass surgery can work in severely obese people—apart from the fact that it reduces the carrying capacity of the stomach—is that it also appears to turn down the ghrelin spigot. An Italian study even looked at ghrelin in anorexics and found that levels of the hormone were chronically high—a chemical alarm that the self-starvers trained themselves to ignore. All this research confirmed ghrelin's role in driving appetite, both when we really need to eat and when we merely expect to.

If ghrelin were all there was to it, we and the rats would eat ourselves to death. But even as one system is gunning our hunger higher, another is standing by to slow things down. The first step in that appetite-taming process occurs in the stomach and upper intestine, where nerves that sense stretching and distension eventually alert the brain that we're getting full. That message is reinforced by three substances that travel northward from the gut. The first, a peptide released by the upper intestine called cholecystokinin (CCK), is the most fleeting of the three, reaching the brain and increasing the feeling of heavy satisfaction that prods you to push away from the table. But cck does not last long, certainly not long enough to prevent you from eating again well before your body needs more fuel.

Racing in after CCK are two hormones, GLP-1 and PYY, that really slam on the brakes. Produced in the lower gut, they not only tell your brain you've had enough but also tell your stomach to stop what it's doing and not move anything further along into the intestines—where the real business of digestion takes place—until what's there has been broken down some. If you've ever finished a heavy meal at 8:30 p.m. and realized that you still feel stuffed when you climb into bed at 11, that's why. What's more, GLP-1 adjusts blood chemistry, stimulating the pancreas to release more insulin, which soaks up sugars released into the blood by the inrushing food and stores them in the body's fat deposits. "These two hormones go beyond meal intake and regulate overall energy balance," says Hans-Rudolf Berthoud, head of the neurobiology and nutrition laboratory at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, La.

If despite all those obstacles in the path of overeating you still pack in too much food—and as a result pack on too much fat—the body has one other, much bigger gun it can roll out: leptin. An appetite-suppressing hormone discovered in 1994, leptin is produced by body fat itself, usually in direct proportion to how much of the tissue you're carrying. The fatter you are, the more leptin you produce. Once in the bloodstream, the hormone travels to the hypothalamus, one of the same brain regions targeted by ghrelin, seeks out a pair of neuropeptides known to stimulate appetite and partly muffles their signals. The result is, or should be, that fatter people want to eat less. Not surprisingly, the discovery of leptin was huge news in the diet community. Maybe obese people were simply suffering from a shortage of leptin; supplement the hormone with periodic injections, and the fat would dissolve away.

As it turned out, things weren't so easy. For one thing, there are hundreds of millions of obese people in the world, but even after 13 years of study, researchers have found only a handful—on the order of 10 to 20—with a congenital deficit in leptin production or function. In fact, the leptin system in most overweight people works precisely the way it's supposed to, with hormone levels climbing more or less in lockstep with weight. The problem is, at some point the stuff simply stops working—or at least stops keeping pace with the numbers on the scale. When the few people born with a leptin deficit are given supplemental injections, they respond to the treatment. But in other obese people—whose systems have been overexposed to the hormone over the years and thus grown resistant to it—the treatments do no good at all. (Some studies show that leptin sensitivity can be improved by dieting and losing body fat, making supplements a little bit more effective.)