Somewhere in your brain, there's a cupcake circuit. how it works is not entirely clear, and you couldn't see it even if you knew where to look. But it's there all the same—and it's a powerful thing. You didn't pop out of the womb prewired for cupcakes, but long ago, early in your babyhood, you got your first taste of one, and instantly a series of sensory, metabolic and neurochemical fireworks went off.

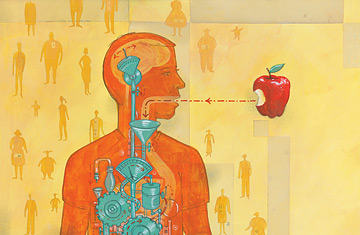

The mesolimbic region in the center of your brain—the area that processes pleasure—lit up. The vagus nerve flashed signals to the stomach, which began to secrete digestive acids. The pancreas began churning out insulin. The liver cranked up to refine the body's chemistry to accommodate the sugar and fat and starch that were coming in. As all those complex processes were unfolding, your midbrain filed away a simple, primal, unconscious idea: Cupcakes are good. A lifetime love affair—perhaps pleasant, perhaps tortured—began.

Human beings have always had a complicated relationship with food. Staying alive from day to day requires our bodies to keep a lot of systems running just so, but most of them—circulatory, respiratory, neurological, endocrine—operate automatically. Eating is different. Like sex, it's a voluntary thing. And like sex, it's a sine qua non to keep the species going. So nature cleverly rigs the game, making sure we pursue them both by making sure we can't resist them. In the case of food, that has lately spelled trouble. Human history has usually been characterized by too little to eat rather than too much. Nature never planned for what could happen when unchecked appetites were suddenly matched by unchecked resources. But we're seeing it now.

Postindustrial humans—as any trip to an all-you-can-eat buffet will tell you—have become a soft, sedentary, overfed lot. It's not just that 67% of the U.S. population is either overweight or obese (including about 17% of children ages 6 to 19); it's that we know that fact full well and seem helpless to control ourselves. We lose weight and routinely regain it; we vow to eat healthfully and almost always lapse. Our doctors warn us about our rising blood pressure and creeping cholesterol, and we get briefly spooked—until we're offered the next helping of cheesecake or curly fries, our appetite shouts down our reason and before we know it, we're at it again. By some estimates, Americans are collectively more than 5 billion lbs. overweight. While in a population of 300 million people that's a more or less manageable 17 lbs. apiece, the weight is not distributed equally. Those of us who are overweight are often grievously so. But all of us pay the cost. "That weight is a shared burden," says geneticist and microbiologist Ronald Evans of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, Calif. "Whether it's you or not, it gets factored into the medical health bill."

Just why is our appetite so powerful a driver of our behavior, and, more important, how can we bring it to heel? If that question has long defied easy answers, it's no wonder. Understanding a single biological unit—the heart, the lungs—is hard enough. Understanding a process as complex as appetite—one that involves taste, smell, sight, texture, brain chemistry, gut chemistry, metabolism and, most confounding of all, psychology—is exponentially harder. But science is trying.

Researchers in labs and institutes around the world are peering into the brain to understand the regions where appetite is perceived and satisfied, and pinpointing the receptors on cell surfaces that keep us hungry or get us sated. They're studying the neural wiring of the stomach and intestines, as well as the operation of the genes that drive our appetite, to track how satiety signals are sent and determine why they sometimes get lost. And they're peering back into human history to understand better how we were booby-trapped for overeating from the start and how we might be able, so many eons later, to cut the trip wire at last. "The scourge of body-weight disregulation has become a leading cause of death worldwide," says Dr. David Cummings, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Washington. "Understanding it is perhaps the most compelling agenda in the field of medical research."