(3 of 20)

Since no outsider can ever really know what goes on in China, I had to content myself for almost two months with assembling fragments of reality, sifting gossip from apparent fact in trying to find out. Of the governing regime in China today, it may be said:

> The old soldiers who have recaptured control are engaged in the most delicate of political tasks, transfer of power. This transfer is not only from one generation to another but is cultural, military, academic, a shift from one set of elites to another.

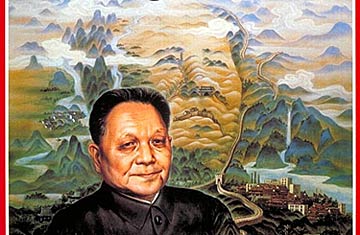

> It is in America's interest that the Deng Xiaoping regime continue its reforms and peacefully transfer power. In the long run, the progress of Chinese science, technology and industry may challenge America as much as Japan has. But, in the short run, the present transition regime works to the world's good. present transition regime works to the world's good.

> This regime acknowledges the Communist Party to be guilty of sins against conscience and history. It has published an official confession, a story of terror and error, in an effort to set up reasonable government.

> Yet always it must be remembered that the old zealots of this regime are married to the thought of unending revolution and still seek to bring Taiwan-back under their flag before they pass on. We have fought one war directly with the Chinese (in Korea) and another by proxy (in Viet Nam); a third confrontation should be avoided at all costs.

GLORY YEARS, NIGHTMARE YEARS

My last previous visit to China was with Nixon in 1972. We knew nothing of what was going on. I tried then to telephone an old friend and was told, "He's not home." When would he be back? "Not certain." This time I found him, and he told me where he had been when I last called: in solitary confinement in a Peking jail from 1968 to 1973. His wife, too, had been in solitary in the same jail. No charge had been brought against either of them, only that he was "under investigation." Greater horrors were taking place in China at the moment of the Nixon visit — hero leaders killed or forced to suicide; tens of thousands of China's best in jail or enduring savage punishment; scores of thousands killed by fanatics; the army called in to restore order where youthful Red Guards had bloodied the streets in civil war.

But of all this we knew nothing in 1972. Something called the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was in full swing. But then, as now, it was as if we were feeling through a membrane: we could sense shapes, forms and fears, almost touch them. But we could not see through the membrane.

Peking now is, to the eye, a far better place. The city's long avenues of young trees, its handsome new architecture, its broad esplanades all promise coming splendor. The people are well dressed. Well-marked buses course their routes — on time. Men and women are healthy; the children are cherubs; the parks are flecked with the colors of young couples courting or families airing babies. The stores are well stocked, from dumplings to ducks. Bookstores are crowded, moviehouses and theaters jammed. Color