(14 of 20)

Chinese officials insist that the transfer of power from one generation to another is irrevocable. If one believes them, as they try to believe themselves, then this new National People's Congress may have real power, may mark a change to a Chinese system of checks and balances, Congress checking on government, both checking on party, party interacting on both.

But what if the new Congress is only window dressing, a facade like those before it? To whom, then, will power pass as the old men die off? Does this Congress dare test its will against the will of the party? What haunts thoughtful Chinese and foreign diplomats alike is the guess on the stability of the new regime. How many old hatreds, old scores sputter in opposition to the new course?

THREATS, "RIGHT" AND "LEFT"

The simmer of unrest in China, The simmer of unrest in China, the undersputter, is pervasive. There comes first, when one looks for opposition, the old Red Army. Trained in combat, promoted by victory, its leaders were men of capacity and command. Slowly, so as not to disturb a slumbering volcano, the aging commanders are being urged out. Retirement is greased with comforts: full pay, choice of home anywhere in China, honors and consultancies. The murmur of envy puts it that such retired generals are guaranteed fangzi, chezi, haizi — quarters at least as good as those they enjoyed as commanding generals, car and driver for life, preference for their children in schools and army.

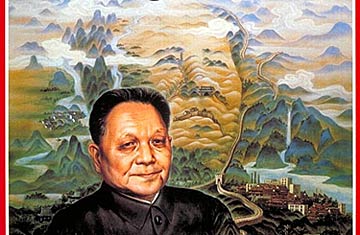

But detachment from privilege and authority disturbs old men. The army was, in its beginning, the people in arms. Then it became a state within a state, submitting its own budget each year; the official planning authority scrutinized its demands but always approved them. Now, under the new constitution, the "government" theoretically must approve the army's military budget. That way lies trouble, as any American Secretary of Defense can testify. Deng Xiaoping is chief of the party's military commission, which promotes, demotes, transfers and appoints the senior commanders of China's eleven military regions. But the new constitution gives the Congress a military commission too. Since Deng chairs both commissions, all is well momentarily; and the six men of the party's Standing Committee all came out of the ranks. So long as such men control, the Congress will do as they say. But the six old men cannot last forever. Thus it disturbs some important generals that nominal authority has been transferred to the Congress.

The party, too, is restless. Buried deep in the ranks of its 35 million to 40 million members are old careerists and rice-bowl men who grabbed offices during the Cultural Revolution. Many have been forced out. But millions remain, and they must somehow finally be ousted. A purge is scheduled for late this year. Party cells are already being called together to restore the shattered morale of all those who were once willing to give their lives to high purpose but who