(13 of 20)

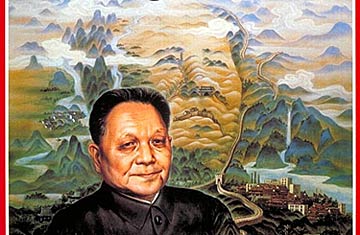

No group could be more sensitive to the changes required by the transition to an "enterprise" system than the six old veterans of the Standing Committee. Life hurries them on; age presses them. They need new, younger men in the party, in the provinces, in industry. And they must choose their replacements, managers, engineers, scientists, now.

PASSING THE BATON

Transfer of power is particularly dangerous in China, where traditionally it went hand in hand with humiliations and killing. The pattern was quite simple. Warriors conquered power, then found it would not function without scholar-bureaucrats, "mandarins." The aging warrior-leaders of the Standing Committee know they too must create a mandarinate. A few years ago, thinkers and scholars were "stinkers"; today, they are desperately needed. But can the old men shift power to them without upheaval?

The transfer of power is now going on as far down as the six-man oligarchy of Peking can reach. But it is so delicate that their government tiptoes as if through a minefield. To talk about this process, I called on Huan Xiang, a vice president of the Academy of Social Sciences in Peking. Huan too had been humiliated, purged and rusticated. After the Gang of Four was wiped out, he came back to Peking. The old soldiers knew that matters had gone wrong —but only scholars could say how and why. So they called in the scholars, Huan among them, to analyze the disaster.

Then the scholars offered suggestions. Students at universities must be admitted only after tests of competence, not because of party loyalty or class background. Industries must be organized not to meet quotas but to meet need. Planning must fit reality. Most important: peasants must be released from state planning to plant their own crops.

The scholars suggested that the party too had to change. There should no longer be one total authority compelling every unit of the state, from commune to city to Peking, to zig or zag every time the party zigged or zagged. The party's function is to lead. The government has another function: to keep order. Enterprise has yet another function, from village field to factory floor: to produce. Now the entire country was living through experiments, said Huan, trying to separate party apparatus from governing apparatus.

As I traveled the interior, hotels were crowded by provincial party caucuses and provincial "people's" congresses, assembled to follow the new party line — dismantle, restructure, reorganize. Out of this effort has since come the new National People's Congress. It is difficult to measure the change in texture from the last session of the Fifth Congress (December 1982), for Chinese sources either