(6 of 11)

Those events awakened long-slumbering Negro resentments, from which a fresh Negro urgency drew strength. For the first time, a unanimity of purpose slammed into the Negro consciousness with the force of a fire hose. Class lines began to shatter. Middle-class Negroes, who were aspiring for acceptance by the white community, suddenly found a point of identity with Negroes at the bottom of the economic heap. Many wealthy Negroes, once reluctant to join the fight, pitched in.

Now sit-in campaigns and demonstrations erupted like machine-gun fire in every major city in the North, as well as in hundreds of new places in the South. Negroes demanded better job opportunities, an end to the de facto school segregation that ghetto life had forced upon them. The N.A.A.C.P.'s Roy Wilkins, a calm, cool civil rights leader, lost some of his calmness and coolness. Said he: "My objectivity went out the window when I saw the picture of those cops sitting on that woman and holding her down by the throat." Wilkins promptly joined a street demonstration, got himself arrested.

"Free at Last." Many whites also began to participate, particularly the white clergy, which cast off its lethargy as ministers, priests and rabbis tucked the Scriptures under their arms and marched to jails with Negroes whom they had never seen before. The Rev. Dr. Eugene Carson Blake, executive head of the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., declared: "Some time or other, we are all going to have to stand and be on the receiving end of a fire hose." Blake thereupon joined two dozen other clergymen in a protest march—and was arrested.

In the months following Birmingham, Negroes paraded, demonstrated, sat in, stormed and fought through civil rights sorties in 800 cities and towns in the land. The revolt's basic and startling new assumption—that the black man can read and understand the Constitution, and can demand his equal rights without fear—was not lost on Washington. President Kennedy, who had been in no great hurry to produce a civil rights bill, now moved swiftly. The Justice Department drew up a tight and tough bill, aimed particularly at voting rights, employment, and the end of segregation in public facilities.

To cap the summer's great storm of protest, the Negro leaders sponsored the now famous March on Washington. It was a remarkable spectacle, one of disorganized order, with a stateliness that no amount of planning could have produced. Some 200,000 strong, whites and blacks of all ages walked from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. There, the Negro leaders spoke—Wilkins, A. Philip Randolph, Young and SNICK's Lewis.

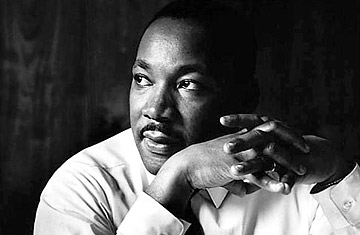

But it was King who most dramatically articulated the Negro's grievances, and it was he whom those present, as well as millions who watched on television, would remember longest. "When we let freedom ring," he cried, "when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing, in