(3 of 11)

Mencken had never met the King family of Atlanta. King's maternal grandfather, the Rev. A. D. Williams, was one of Georgia's first N.A.A.C.P. leaders, helped organize a boycott against an Atlanta newspaper that had disparaged Negro voters. His preacher father was in the forefront of civil rights battles aimed at securing equal salaries for Negro teachers and the abolition of Jim Crow elevators in the Atlanta courthouse.

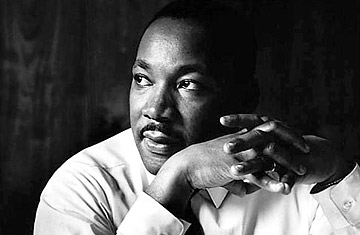

As a boy, Martin Luther King Jr. suffered those cumulative experiences in discrimination that demoralize and outrage human dignity. He still recalls the curtains that were used on the dining cars of trains to separate white from black. "I was very young when I had my first experience in sitting behind the curtain," he says. "I felt just as if a curtain had come down across my whole life. The insult of it I will never forget." On another occasion, he and his schoolteacher were riding a bus from Macon to Atlanta when the driver ordered them to give up their seats to white passengers. "When we didn't move right away, the driver started cursing us out and calling us black sons of bitches. I decided not to move at all, but my teacher pointed out that we must obey the law. So we got up and stood in the aisle the whole 90 miles to Atlanta. It was a night I'll never forget. I don't think I have ever been so deeply angry in my life."

Ideals & Technique. Raised in the warmth of a tightly knit family, King developed from his earliest years a raw-nerved sensitivity that bordered on self-destruction. Twice, before he was 13, he tried to commit suicide. Once his brother, "A. D.," accidentally knocked his grandmother unconscious when he slid down a banister. Martin thought she was dead, and in despair ran to a second-floor window and jumped out—only to land unhurt. He did the same thing, with the same result, on the day his grandmother died.

A bright student, he skipped through high school and at 15 entered Atlanta's Negro Morehouse College. His father wanted him to study for the ministry. King himself thought he wanted medicine or the law. "I had doubts that religion was intellectually respectable. I revolted against the emotionalism of Negro religion, the shouting and the stamping. I didn't understand it and it embarrassed me." At Morehouse, King searched for "some intellectual basis for a social philosophy." He read and reread Thoreau's essay, Civil Disobedience, concluded that the ministry was the only framework in which he could properly position his growing ideas on social protest.

At Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pa., King built the underpinnings of his philosophy. Hegel and Kant impressed him, but a lecture on Gandhi transported him, sent him foraging insatiably into Gandhi's books. "From my background," he says, "I gained my regulating Christian ideals. From Gandhi I learned my operational technique."

Montgomery. The first big test of King's philosophy—or of his operating technique—came in 1955, after he had married a talented young soprano named Coretta Scott and accepted the pastorate of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala.

On Dec. 1 of that year, a seamstress