(4 of 11)

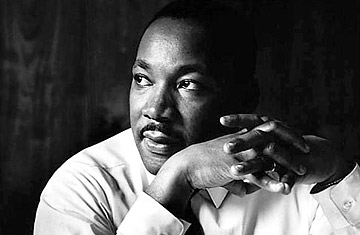

For some reason, that small incident triggered the frustrations of Montgomery's Negroes, who for years had bent subserviently beneath the prejudices of the white community. Within hours, the Negroes were embarked upon a bus boycott that was more than 99% effective, almost ruined Montgomery's bus line. The boycott committee soon became the Montgomery Improvement Association, with Martin Luther King Jr. as president. His leadership was more inspirational than administrative; he is, as an observer says, "more at home with a conception than he is with the details of its application." King's home was bombed, and when his enraged people seemed ready to take to the streets in a riot of protest, he controlled them with his calm preaching of nonviolence. King became world-famous (TIME cover, Feb. 18, 1957), and in less than a year the Supreme Court upheld an earlier order forbidding Jim Crow seating in Alabama buses.*

Albany. Montgomery was one of the first great battles won by the Negro in the South, and for a while after it was won everything seemed anticlimactic to King. When the sit-ins and freedom-ride movements gained momentum, King's S.C.L.C. helped organize and support them. But King somehow did not seem very efficient, and his apparent lack of imagination was to bring him to his lowest ebb in the Negro movement.

In December 1961, King joined a mass protest demonstration in Albany, Ga., was arrested, and dramatically declared that he would stay in jail until Albany consented to desegregate its public facilities. But just two days after his ar rest, King came out on bail. The Alba ny movement collapsed, and King was bitterly criticized for helping to kill it.

Today he admits mistakes in Albany.

"Looking back over it," he says, "I'm sorry I was bailed out. I didn't under stand at the time what was happening.

We thought that the victory had been won. When we got out, we discovered it was all a hoax. We had lost a real opportunity to redo Albany, and we lost an initiative that we never regained."

But King also learned a lesson in Albany. "We attacked the political power structure instead of the economic power structure," he says. "You don't win against a political power structure where you don't have the votes. But you can win against an economic power structure when you have the economic power to make the difference between a merchant's profit and loss."

Birmingham. It was while he was in his post-Albany eclipse that King began planning for his most massive assault on the barricades of segregation. The target: Birmingham, citadel of blind, diehard segregation. King's lieutenant, Wyatt Tee Walker, has explained the theory that governs King's planning: "We've got to have a crisis to bargain with. To take a moderate approach, hoping to get white help, doesn't work.