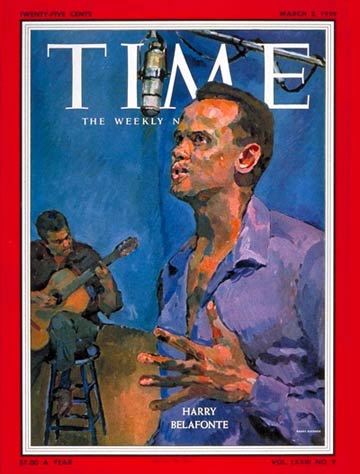

Harry Belafonte

(5 of 8)

Harry stayed there until he was 13; after their mother returned to New York, the boys were boarded out with relatives or at a succession of schools. It was a lonely time but also an exciting one. "I still have the impression," Belafonte says, "of lush green vegetation, white sandy beaches, rolling surf, endless winding roads. It was an environment that sang." The people sang with it. The streets of Kingston were thronged with piping vendors or politicians drumming up a vote in the lilting singsong of the islands. It was "a groovy time. I was a great night gazer. I used to climb up in a mango tree and lie back and eat mangoes and look through the leaves at the sky."

When Mel vine Belafonte brought Harry and Dennis back to Harlem, they moved into a white neighborhood, where Harry passed for a time as a "Frenchy" from Martinique. But he could not keep it up: "Once I got really hot and spilled the beans." After that, the fights were more frequent and more vicious than ever. Belafonte still bears a few of the scars of street combat, but, he says, "the emotional scars were worse. I was good at sports, and when they chose up sides they always chose me first. I was accepted then, but it never carried over. I would be sitting there on my stoop, and I'd see the guys going by all dressed up on their way to a party. They never asked me."

Over the River. When he was 16, Harry got fed up, left George Washington High School, and six months later joined the U.S. Navy. The experience, he remembers, was "like taking a deep breath." Assigned in 1944 to an all-Negro unit, many of whose members were college graduates, he became interested for the first time in Negro history. The other highlight of his naval career was his meeting with a well-to-do Negro girl named Frances Marguerite Byrd, who was a student at Virginia's Hampton Institute, where Harry was in training. He immediately recognized her as "everything I ever wanted," assured her that she would marry him some day, and departed for more training on the West Coast, leaving her with his signet ring, a gold locket and a white poinsettia. He served in the Navy as a storekeeper, was discharged after 18 months without ever getting overseas.

Back in Harlem, Belafonte worked as a handyman in tenement houses, toyed with the idea of becoming either a professional basketball player or a social worker, finally drifted into the theater by accident. (The occasion: he got two tickets to an American Negro Theater production as a tip for repairing Venetian blinds.) He worked as a stagehand at the theater, appeared in a few minor roles. Soon after that, he enrolled in the Dramatic Workshop at Manhattan's New School for Social Research, where his classmates included Marlon Brando and Tony Curtis. Harry also persuaded Marguerite to marry him one evening in 1948 by swinging her over a parapet by the East River and holding her suspended over the water until she said yes. "I married him," she now explains, "because I felt that if I didn't, he was going to turn delinquent."