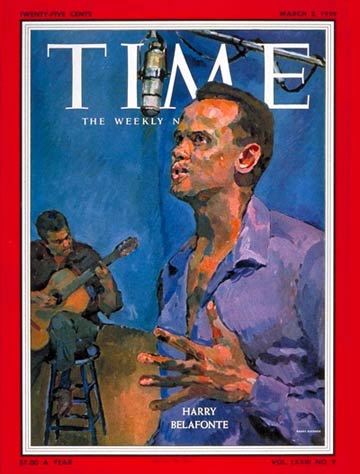

Harry Belafonte

(4 of 8)

Emotional Gap. If a traveler with a tape recorder were to take down some of the folklore that is growing up about Harry Belafonte himself, not all the sounds would be pleasant. There are some tom-toms of jealousy. A discarded former agent says: "I hate him. We had a very close relationship, but how could I know he was going to turn into an Emperor Jones?" There are some mocking ditties to the effect that he takes himself too seriously. There is the blues of his first wife Marguerite, a former school teacher in Manhattan, who says: "I remember when he used to speak about not being hired because he was a Negro. Now his secretary in New York is white."

Actually, Belafonte remains proudly self-conscious of being a Negro, turned down the part of Porgy in Samuel Goldwyn's production of Porgy and Bess because he felt that Catfish Row presented Negroes in an undignified light. He talks in analytically flavored prose about "Negro situations" and says: "In 1944, with three other Negro sailors and our dates, I was refused a table at the Copacabana. Nine years later I was back there as the headliner. How do you bridge that gap emotionally?" Asked about his second marriage, to a white girl, he says stiffly that the race question docs not matter: "I don't want to be anybody's brother-in-law. I just want to be his brother."

But along with such talk, he has an engaging ability to kid himself, and his concerns. Once he saw a nature movie about a herd of brown deer with white markings in whose midst appeared a mutation—a white deer with brown markings. "You see," purred the narrator, "he's playing right along with the other deer and they don't even seem to notice the difference." Said Belafonte with a laugh loud enough for the whole theater to hear: "Boy, they're well integrated." In his playful moods, Belafonte is also fond of fabricating stories about himself and his family. For a time he informed strangers that his present wife was an American Indian and that he was a former resistance fighter with the Hagana in Israel.

Singing Environment. Actually, his story needs no fanciful embellishments. Harold George Belafonte Jr. was born 32 years ago in Harlem, son of a seaman in the British merchant marine; his mother was alternately a dressmaker, a baby sitter, a domestic servant. Both parents came from Jamaica, West Indies, and both were products of white and Negro unions. Harry's father disappeared when he was two (he reappeared sporadically after that), and Harry was brought up by his mother in a succession of Harlem tenements. At his first school (P.S. 186, on 145th Street and Amsterdam Avenue),

Harry learned something about the problems of being a Negro in a fringe neighborhood: "I grew up fighting. I fought about the little children's nursery rhymes; I fought about 'eeny, meeny, miney, mo'; I fought about being bumped in the hall. We fought with bottles, garbage cans, rocks, hands and feet." Off and on, Harry ran with the gangs—the Buccaneers, the Midtown Midgets. When the streets became too dangerous and the Depression too tough, his mother packed up nine-year-old Harry and his younger brother Dennis and returned to Jamaica.