Harry Belafonte

(2 of 8)

Belafonte was the first Negro to perform in such plush nightspots as the Eden Roc in Miami and the Palmer House in Chicago. He is the only American Negro to be cast in a romantic movie role opposite a white actress (Joan Fontaine in Island in the Sun). He has not only crossed some color lines, but a great many other lines as well. His appeal is remarkably independent of age or sex. In a recent concert in Pittsburgh, he packed the hall with steelworkers. symphony patrons, bobby-soxers and schoolchildren. When he toured Europe last summer for the first time, he broke attendance records everywhere he sang. "I can play Belafonte," says Manhattan Disk Jockey William B. Williams, "and not lose any part of the audience."

What does he have that the public wants? To begin with, as he says himself, "there are certain things there physically that I can't help: height, looks, youth." Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt has written about his ability to mesmerize an audience, while Singer Diahann Carroll says in a more lyrical vein: "From the top of his head right down that white shirt, he's the most beautiful man I ever set eyes on."

Then there is that voice. It is not trained (he does not read music), and Belafonte subjects it to growls, yelps and shouts that appall the opera stars who come to hear him. The voice can become gutty as a trumpet, musky with melancholy, or high and tremulous as a flute. It may take on the high, clipped inflection of the West Indies, the open-throated drawl of the bayou country, the softly rounded burr of the Scotch borderland.

But there is more to Belafonte than looks and voice. Each of his performances is a brilliantly planned and executed combination of artistry and showmanship.

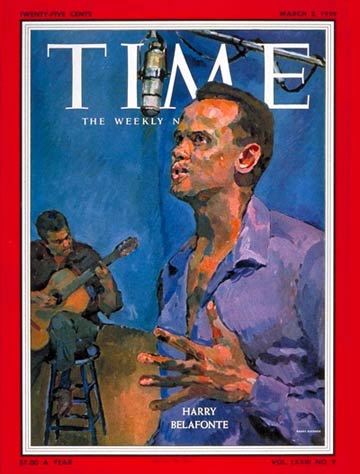

Upbeat Pink. Belafonte usually strides on stage in pitch blackness, stations himself by the microphone before the spotlight bursts on him—light blue, lavender or "upbeat pink," depending on the mood he is trying to convey. For his female fans the famed Belafonte costume—a tailored ($27) Indian cotton shirt partially open, snug black slacks, a seaman's belt buckled by two large interlocking curtain rings—combines the dashing elegance of a Valentino cape with the muscled fascination of a Brando T shirt. The handsomely chiseled head is tipped slightly back, the eyes nearly closed. He is always backed by two guitars, a bass fiddle and a conga drum, to which may be added other instruments, or a full orchestra, or a twelve-man chorus.

He usually opens on a serious note, a protest song that may be Jerry or Darlin' Cora or Tol' My Captain. He goes on from there to shouters (Lead Man Holler), love songs (I Do Adore Her), songs of thanksgiving (Merci Bon Dieu), an Israeli Hora (Hava Nageela). Belafonte has developed a remarkable emotional pantomime to match the content of his songs. In John Henry, he hunches his tall, lithe body (6 ft. 2 in., 185 Ibs.) in a half crouch, knots his fists, launches into the verses with teeth clenched and a spasmodic toss of his head:

John Henry he could hammer He could whistle, he could sing.