Tim Campbell, senior vice president of air operations for American Airlines, is staring at a diagram of the Charlotte, N.C., airport. It shows the position of the carrier's jets on the tarmac--the flights that haven't already been canceled, that is--and how quickly they're getting through deicing stations, since a traffic jam will slow everything down. So far, no jets are backed up; in fact, some of the deicers are idle. "I was questioning whether we maybe canceled too much," he admits. But events prove otherwise: only half the airport ground crews will make it to work on this Wednesday in early February, as Charlotte is buried beneath a winter storm that is churning its way up the East Coast, bound to cancel flights by the dozen.

Now is the winter of our disconnects. And cancellations. And getting stuck in faraway places with no fast way home. A single snowy week in February saw more than 14,000 flights canceled, among the nearly 79,000 erased by a series of winter storms that are partly the product of a weather phenomenon called the polar vortex. More flights have been grounded this winter than at any time since 1987, when the Department of Transportation first started collecting data. An additional 290,000 have been delayed, according to flight-tracking website FlightAware.

But the weather alone does not explain why on any given day, tens of thousands of passengers may find themselves stranded and scrambling to make their way home. The cancellation crisis also reflects how drastically the airline business has changed in the past decade. After 9/11, after the Great Recession, after bankruptcies and consolidations, the airlines have bounced back, stronger than ever but also more disciplined. Serial mergers have left Americans with just three legacy carriers, which means redundant or unprofitable flights are scrapped and planes are more crowded. Tight schedules and turnarounds mean a thunderstorm blowing through Newark, N.J., can radiate cancellations across the country, leaving customers stranded when other planes are too full to accommodate them. And new government regulations designed to prevent passengers from being held captive on the tarmac carry such hefty fines that airlines are more likely than ever before to cancel delayed flights.

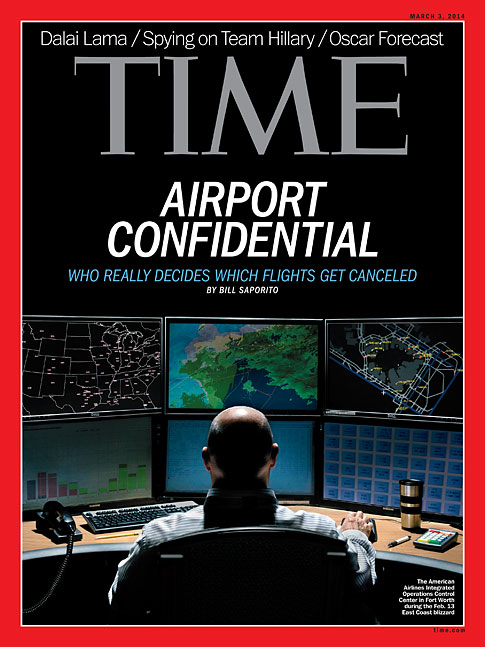

But who, amid the enraged tweets and forlorn Instagrams, actually decides which flights will live or die? In 2014 that decision is being made by an algorithm--with input from human operators--that tries to weigh which flights can be shelved while keeping an airline's schedule as whole as possible. American Airlines' employees even have a nickname for their program: the Cancellator. The Cancellator--and programs like it at other airlines--attempts to keep the chaos in the system to a minimum even as it maximizes the headaches for the unlucky. The idea is to use predictive models to cancel flights early, before people even leave for the airport. "We will do anything possible to avoid real-time cancellations," says Rob Maruster, chief operating officer of JetBlue, which runs a similar program. "Nobody likes people standing in the airport watching real-time cancellations happen." Instead, reaccommodation programs can rebook passengers automatically if they've set up that function on the airline's website.