(4 of 6)

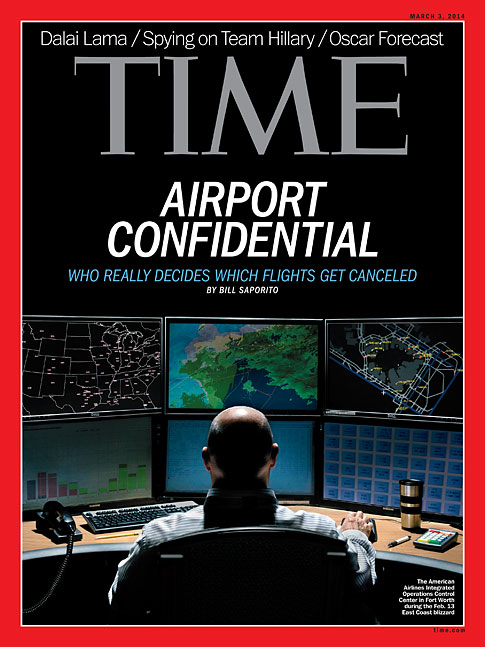

Back on the floor of American's Control Center, Schulz, Szendrey and their colleagues patch the system together as it begins to fray. The pair can claim more than 65 years of service at American between them, having worked everywhere from reservations to crew scheduling. They hold federal aircraft-dispatcher licenses, and like most of the people in the room are union guys, represented by the Transport Workers Union, which engaged in ferocious battles with American's former management. Since American's merger last year, US Airways' top managers are running the show, and there's quiet on the labor front for the first time in decades.

The weather is always throwing the Cancellator curves. In Washington on Wednesday, airport authorities can't get the runways cleared; on Thursday flight dispatchers can't get to work; in Newark, a shortage of TSA workers means that only one security lane is open in Terminal C, delaying flights for hours. A week earlier in Dallas, even though ice was cleared from the runway after a storm, the tugs that normally push planes away from the gate couldn't get enough traction to haul the big Boeing 777s out of their hangars.

Then another, somewhat unusual problem turns up on the screen: Vice President Joe Biden is flying to Miami, an American hub, and Air Force Two demands restricted airspace for security. This slows down other traffic. But Biden is running a half-hour late, so he's delaying more flights than controllers had originally planned. "Our big issue was Biden flying down to Miami. He likes to land in Miami and disrupt our hub," says Szendrey, with obvious irony. At the same time, a squall line is bearing down on western Florida, further diverting flights on a day that hardly needed more hair balls. By Wednesday afternoon, the Cancellator has been scratching flights from Miami all the way up to Boston.

One of the command center's main missions is to limit the number of delay minutes and misconnects, which are tracked continuously. While we're looking at the weather and traffic heading to Miami, Schulz points out Flight 1266 from New Orleans, which has six misconnects on it--Miami-bound passengers headed for South America who are going to miss their connecting flights. The plane is currently routed east-northeast out of New Orleans, veering south when it hits Georgia. Why doesn't the jet fly straight across the Gulf of Mexico? I ask. Earlier in the day, the weather was too severe, but Schulz queries the system again and the computer reroutes the flight. Six misconnects saved.