(2 of 6)

And yet the sheer size of the problem is beyond calculation. "There's nothing that solves for all the factors," says aviation expert Blair Pomeroy of consultancy Oliver Wyman. Our civil aviation system works no better than "just O.K." on a perfect day--without weather, without labor issues, without mechanical malfunction. But on a bad day, like the one I spent witnessing the operation of American's command center, the whole thing can grind to a halt. Turns out, the cancellations most travelers experience as random and cruel are anything but.

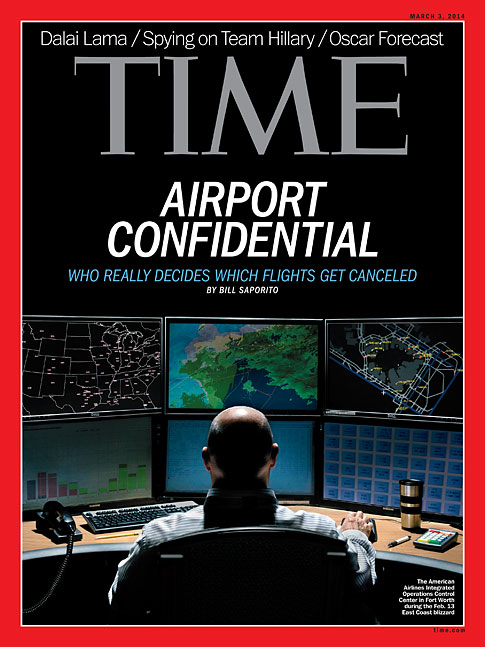

On the afternoon of Feb. 12, American's integrated Operations Control Center just outside the Dallas--Fort Worth airport gives no hint that the Atlantic Coast is choking on snow and ice. The crisis room that hovers like a skybox above the 36,340-sq.-ft. (3,376 sq m) nerve center is empty. The main floor is a trading pit of meteorologists, airport managers, flight-attendant supervisors, crew schedulers, customer-service teams, diversion coordinators, specialists in each type of jet that American flies, maintenance and parts trackers, flight-operations engineers and other groups needed to keep what is now the world's biggest airline aloft. In a centrally located pod designated for American's air-traffic dispatchers, Ron Schulz and Billy Szendrey are manning the desk. They are, for this eight-hour shift, the masters of the Cancellator.

On one monitor they track federal air-route operations, which has information about airport conditions, traffic patterns, ground delays and gate capacity. Another screen shows the positions of all aircraft, superimposed over the weather radar. It's looking grim. On a third, there's a live view of how well American is performing in the midst of all this. It tracks metrics by airport and flight, gathering arrival and departure data, flight-delay minutes, passenger-delay minutes and whether crew members are in danger of reaching their hourly work maximums. A big issue when storms hit is that planes and crews end up in far-flung places, and retrieving them is time-consuming and expensive.

Schulz and Szendrey are constantly monitoring all these variables and feeding them into the Cancellator. Schulz looks at Chicago and sees 31 misconnects, meaning passengers who will miss their next flight the way things are going. Running a simulation, he can ask the program what would happen if, say, he adds 120 minutes to an outbound flight--that is, delay it until feeder flights catch up. How many customers would make their connection? Would any crew member have worked so many hours that they are close to a violation?

Before any big storm, the Cancellator proposes a hit list on its own, which Schulz and Szendrey fine-tune. It's a big change from just a couple of years ago, when the two men were the ones making the call based on their own experience and then typing in the cancellations themselves. Today, once a plan is set in motion, the flight dispatchers look for options or exceptions the Cancellator didn't spot, or react to rapidly changing conditions. "We'll modify it--not that one, this one," says Szendrey. "The computer may have canceled two flights in a row to the same destination. Sometimes we can take that out of the equation."