(5 of 7)

After the initial presentation, a reporter asks the mayors to speak in general about the importance of private philanthropy, a tradition that is far more developed in the U.S. than in Europe. Bloomberg takes the bait. It's a topic on which he has thought quite a bit. "You can do things that the public does not think are appropriate or conventional for public moneys," he says. "If we didn't have private philanthropy, you never would have had Impressionism, for example. Nobody thought that that was art, and today that commands prices 10 times that of the old masters."

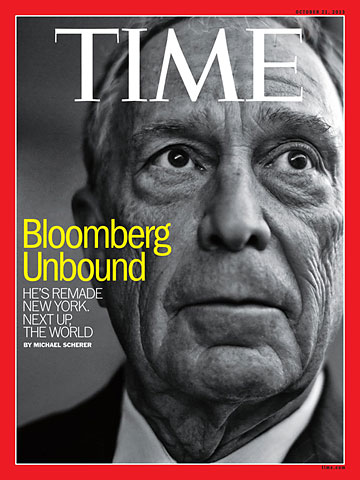

This conviction, that big money should operate independently of public opinion, is at the core of Bloomberg's philosophy, and it is the reason so many people have come to regard him as a cause for concern. In conservative circles, he is the poster child of the nanny state and a punch line for Sarah Palin's road show, the ultimate big-city elitist in monogrammed shirts imposing his will on a freedom-loving country. Two states, Mississippi and North Carolina, have passed anti-Bloomberg laws that prevent their cities from banning soda drinks sold in supersize containers, undermining another project of the mayor's. Both Virginia and West Virginia have passed laws to outlaw Bloomberg's pet practice of hiring private investigators to show how easy it is to buy guns outside the law at high-traffic gun stores.

Bloomberg takes all the populist backlash as validation. He talks of tobacco firms and soda companies like Coca-Cola and Pepsi as enemies of long life. And he is open in his condescension for those who resist the data on which he bases his decisions. "I feel sorry for the people of Mississippi," he says later, when I mention the legislation there to ban restrictions on soda size. In New York City, life expectancy is now above 80. "In parts of Mississippi, by the delta, it's in the 60s. Now what did I miss here? Who's right, and who's winning? They are not winning."

At the center of Bloomberg's worldview is a notion that he exists beyond the baser irrationality of the political process. When he wrote his memoir in 1997, he spoke of the importance of having a loyalty to a political party, saying he sometimes supports Democrats "even when I don't really believe they are the best on the ballot." Today he casts himself outside of partisanship and ideology, telling a story about teasing liberal billionaire Soros about being the same as conservative David Koch in his giving. "He had a heart attack, but they are [similar]," Bloomberg says. "Whether one's view is left, one's view is right, so what?"