(4 of 7)

There is no clear limit on how much Bloomberg is willing to spend on politics. His political adviser and deputy mayor Howard Wolfson, a former aide to Hillary Clinton's 2008 presidential campaign, oversees Bloomberg's political spending without an annual budget. "What will it take?" Bloomberg will ask people as they pitch him. And if they digress from the hard numbers into storytelling, Bloomberg will cut them off. "Quit finger painting," he will say.

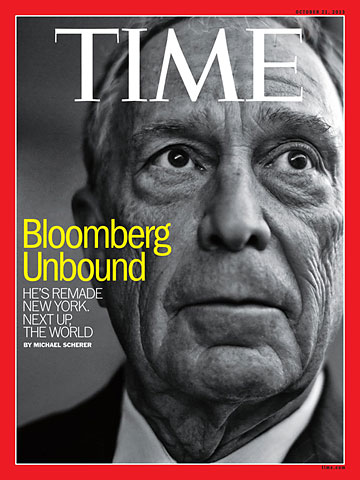

Bloomberg is a data guy, so the numbers matter. When he first ran for mayor in 2001, he was worth about $4 billion, owing to the news and financial-information company he founded that bears his name. When he leaves office on Dec. 31, he will be worth about $31 billion, or about 400,000 times the median American family's net worth. Trust funds have already been established for his daughters and other loved ones, and he is not far from owning as many houses, planes, paintings and sculptures as he needs. The rest he has promised to give away--"bouncing the check to the undertaker," as he puts it.

In 2013, Bloomberg plans to spend about $400 million on pet causes, which at 1.3% of his fortune is barely a rounding error. If his net worth holds steady, or even if it fails to gain a bit of interest over the coming decades, the annual giveaways will have to rise substantially to meet his goal of spending down the fortune in the lifetimes of his daughters, ages 30 and 34. Ask him about the challenge, and Bloomberg will smile. "That's a nice problem to have," he says.

London's city hall is a swirling glass seedpod of a building perched on the Thames. It was designed by British architect Norman Foster, whom Bloomberg happens to have commissioned to create two new buildings for his company a few blocks from the river's far bank. That project is massive, consuming an entire block, and it sits atop an ancient Roman temple where archaeologists have already discovered thousands of artifacts from the first years of the city's existence. Several hundred feet over the site hangs a video camera put there by builders and which Bloomberg, and only Bloomberg, can control from his computer in New York. Most of the time, when he logs in, it's night in London, so the view isn't that great. But such are the hardships of someone with his stature.

Besides, at the moment, he is not far away, having gathered the mayors of London, Warsaw and Florence at city hall to announce a competition offering a €5 million prize for the European city with the most innovative idea to improve local governance. It's a repeat of a competition Bloomberg held in America in 2012, a part of his effort to fund improvements in local governance. The winner of the last prize was Providence, R.I., which will now buy small digital recorders to track the number of words the city's low-income children are exposed to daily. Research has shown that poor kids enter school with a more limited vocabulary, and the goal of the project is to give the tools to their parents to encourage more communication with their children.