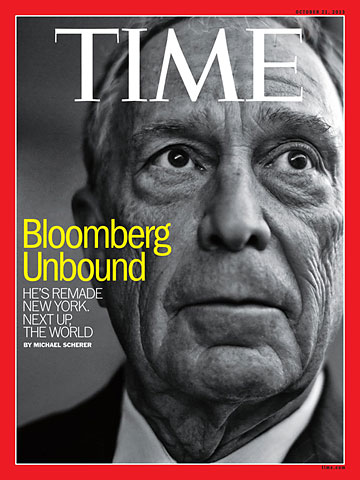

(2 of 7)

For the 16 experts at the table, that's not in question; most of these tobacco fighters have only a single career. But for Bloomberg, the statement is a calculation; his hands are in a lot of different pots and behind a lot of crusades these days. And he is not alone. Over the past 30 years, the world has been transformed by globalization and technology, and from that tumult has emerged a new class of billionaires who profited from the change, innovators, business leaders and heirs. In the prime of their lives, many have turned their attention to remaking the world, often through policy and politics. It's a return to the era of great benefactors like the Rockefellers, Mellons and Carnegies. It's their world. You just vote in it.

The examples are so many, they crowd together. Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg gives $100 million to rewrite the rules for Newark public schools, spends millions more on political television ads and then travels to Congress to demand immigration reform. The casino magnate Sheldon Adelson bets $100 million to elect Republican candidates who mostly lose in 2012, and then publicly vows to do it again. Without financiers George Soros and Peter Lewis, marijuana legalization would not have proceeded so far in so many states. Without the generosity of conservative industrialists David and Charles Koch, the groups now organizing to defund Obamacare would be a shadow of themselves. Without billionaires like Bloomberg, Bill Gates, Eli Broad and Jim Walton, the revolution now taking place in K-12 education--charter schools, standardized tests, Common Core, merit pay, the end of tenure--would be years behind schedule.

Not since the early 20th century have individuals had so much power to unilaterally shape our lives and shift our ideas. And never in history have they been able to exert their will so easily on such a global scale. This is the backdrop upon which Bloomberg is attempting to define his legacy, as a social and political engineer.

"Bouncing the Check"

He makes no secret of his ambition. "I want to do things that nobody else is doing," he told TIME on a two-day swing through Europe in late September, where he met with the mayors of London and Paris and chatted with British Prime Minister David Cameron between visits to art galleries and an antique-furniture dealer. Officially he was still serving as mayor of New York City, but in practice he had already begun his next life, a jet-setting blur of wealth, power and international recognition. He launched a privately funded European competition to improve city governance, boasted of his 17-city international effort to increase volunteerism and reviewed plans to impose further helmet and road-safety laws in the developing world. "A lot of elected officials are afraid to back controversial things. I'm not afraid of that," he said. "You're not going to hurt my business, and if you are, I don't care. I take great pride in being willing to stand up."