(2 of 3)

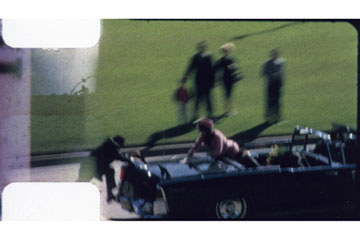

The film advanced to infamous frame 313, and Oswald's bullet struck the President's head. The two agents and I responded precisely the same, with an explosive ugh!, as if we had been simultaneously gut-punched. It was the single most dramatic moment of my 70 years in journalism. The fact that we were watching the assassination only hours after it had occurred was nothing short of remarkable. I decided instantly: There is no way I am going to leave this office without that film.

Zapruder ran the 26-second film for us three times. After that, we could hear a commotion starting in the hall outside. As I had suspected, other reporters were showing up, told (like me) to be there at 9 a.m. In all, two dozen or so arrived, representing the Associated Press, the Saturday Evening Post magazine, a newsreel maker and two or three major out-of-town newspapers. It seems impossible now, but network television never appeared. TV news had only recently gone from 15 minutes in the evening to half an hour, and the three major networks were concentrating their forces on the funeral in Washington, not the crime in Dallas.

Zapruder explained to us that he was going to show his film to these newcomers. The Secret Service agents left, and I asked Zapruder if I could sit in his office and thus be spared mingling with these potential competitors.

During the next hour or so, I introduced myself to and chatted with members of his staff, particularly Lillian Rogers, Zapruder's assistant. She turned out to be from southern Illinois; I was from central Illinois, and a surefire subject of interest to anyone from that state was high school basketball. I had been sports editor of my hometown newspaper, the Pekin Daily Times, and knew that her favorite team, Taylorville High School, was consistently one of the best in Illinois, and said so. We hit it off like old friends--something Zapruder noticed when he came into the office between screenings of the film.

After Zapruder had shown the film to the last reporter, he asked me to join the others in the hall. He said he realized that we all wanted to talk to him about print or broadcast rights, but "because Mr. Stolley of LIFE was the first to contact me, I feel obliged to speak to him first." In my mind, I pumped a fist. The others erupted, shouting, "No, no!" "Don't sign anything!" "Promise you will speak to us before you make up your mind!"

Zapruder agreed, and we walked into his office and closed the door. He looked very tired, but I quickly had to determine whether he realized the value of his film. I said that it was "very interesting" and that when LIFE encountered "unusual" pictures like these, we were inclined to pay higher-than-normal space rates. For example, we would be willing to offer "as much as $5,000" for the film.

He smiled. Yes, he knew what he had. From then on, I would raise the bid, and we would talk, mostly about the tragic weekend. He described a nightmare he had had only a few hours earlier. In it, a man wearing "a sharp double-breasted suit" stood in front of a sleazy Times Square movie theater--midtown Manhattan's Times Square was a porn mecca back then--shouting for people to come in and see the President assassinated on the big screen. He said he woke up shuddering.