'Dick, Kennedy's been shot in Dallas!' I was in my office as Los Angeles bureau chief for LIFE magazine. The shouter was a LIFE correspondent who had wandered over to the Associated Press Teletype to find out (pre-Internet) what was happening in the world.

The AP machine was spitting out bulletins and flashes, with accompanying alarm bells, that gave the first news of the tragedy in Dealey Plaza. I ran to see for myself, then back to my desk to call my editor in New York City and ask what we could do. "How fast can you get to Dallas?" was the answer. An hour later, four of us were on a National Airlines plane.

About 6 p.m. I got a call from Patsy Swank, a part-time LIFE correspondent in Dallas who had spent the afternoon at police headquarters. Her news was astounding. She said another reporter had told her that a cop had told him that a local businessman had been at Dealey Plaza with a movie camera and had photographed the assassination.

Anticipating my next question, she said, "My friend couldn't spell the name, only pronounce it. Za-proo-dur."

I picked up the phone book and ran my finger down the Z's--and there it was, just as Patsy had pronounced it: Zapruder, Abraham. I began calling; I kept on calling every 15 minutes. No one answered. Zapruder, the garment-factory co-owner and 8-mm enthusiast who had unexpectedly captured the President's assassination on camera, was out trying to get his film developed, as I later learned.

Finally, at 11 p.m., a weary voice answered. I asked if this was Mr. Zapruder, and then identified myself and LIFE. I asked if it was true that he had photographed the assassination that morning. "Yes." Did he photograph the whole sequence? "Yes." Had he actually seen the film himself? "Yes." Could I please come to his home now and see the film? "No."

He politely explained that he was exhausted and overcome by what he had witnessed. The decision I made next turned out to be quite possibly the most important of my career. In the news business, sometimes you push people hard, unsympathetically, without obvious remorse (even while you may be squirming inside). Sometimes, you don't. This, I felt intuitively, was one of those times you don't push. I reminded myself: This man had watched a murder. I said I understood. Clearly relieved, Zapruder asked me to come to his office at 9 the next morning.

Saturday Morning

Back in at least a semi-push-hard mood, and being reasonably sure that Zapruder would have talked to other reporters after me on the previous night, I got there at 8. Zapruder looked a little surprised to see me but said he was about to show the film to two Secret Service agents and agreed to let me join. The projector was set up in a small, windowless room, with a white wall serving as the screen.

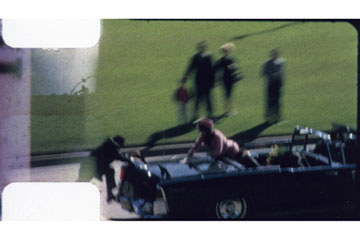

The first few frames showed some of his employees, who had turned out to see the President. Then the motorcade appeared. There was no sound except for the whirring of the projector. We watched transfixed, knowing what was going to happen yet not having a clue as to what it would look like. The limousine was briefly obscured by the road sign, then for a couple of seconds Kennedy clutched his throat, Texas Governor John Connally tipped over, their wives looked puzzled.