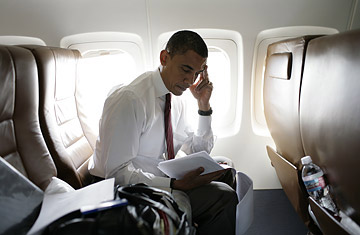

Senator Barack Obama looks over a speech on his campaign plane

(4 of 4)

Back up a few paragraphs and look again at something Obama wrote in his memoir. It's that passing reference to his mother living in a "'60s time warp." No presidential nominee since John F. Kennedy has so lightly dismissed those turbulent years. What could the Summer of Love have meant to a 6-year-old in Hawaii, or Woodstock to an 8-year-old in Indonesia? The Pill, Vietnam, race riots, prayer in school and campus unrest--forces like these and the culture clashes they unleashed have dominated American politics for more than 40 years. But Obama approaches these forces historically, anthropologically--and in his characteristic doctor-with-a-notepad style. In The Audacity of Hope, he writes about the culture wars in the same faraway tone he might use for the Peloponnesian Wars. ("By the time the '60s rolled around, many mainstream Protestant and Catholic leaders had concluded," etc.) These fights belong to that peculiar category of the past known as stuff your parents cared about.

"I think that the ideological battles of the '60s have continued to shape our politics for too long," Obama told TIME. "The average baby boomer, I think, has long gotten past some of these abstract arguments about Are you left? Are you right? Are you Big Government? Small government? You know, people are very practical. What they are interested in is, Can you deliver schools that work?"

This aspect of Obama--the promise to "break out of some of those old arguments"--speaks powerfully to many younger Americans, who have turned out in record numbers to vote and canvass for him. Obama is the first national politician to reflect their widespread feeling that time is marching forward but politics is not, that the baby boomers in the interest groups and the media are indeed trapped in a time warp, replaying their stalemated arguments year after year. The theme recurs in conversations with Obama supporters: He just feels like something new.

Obama on the stump is constantly underlining this idea. As he told a recent town-hall meeting in a New Mexico high school gym, "We can't keep doing the things we've been doing and expect a different result." It's a message his campaign organization has taken to heart. Obama's is the first truly wired campaign, seamlessly integrating the networking power of technology with the flesh-and-blood passion of a social movement. His people get the fact that the Internet is more than television with a keyboard attached. It is the greatest tool ever invented for connecting people to others who share their interests. For decades, the Democratic Party has relied on outside allies to deliver its votes--unions, black churches, single-interest liberal groups. With some 2 million volunteers and contributors in his online database, Obama is perhaps a bigger force now than any of these. McCain may perceive Obama's enormous celebrity as a weakness--workhorse vs. show horse--but celebrity has its benefits. Obama will accept the nomination in front of a crowd of 76,000 in Denver's professional-football stadium, and the price of a free ticket is to register as a campaign volunteer.

Each of the first four Obama faces presents risks for his campaign, but the fifth prospect offers a way around many of them. If he can get through a general-election campaign without enlisting in the culture wars, he gains credibility as something new. That in turn might keep him from becoming mired in the trap of identity politics. Branding himself as the face of the future can neutralize the issue of inexperience. And if he can build his own political network strong enough to win a national election, he will lend credibility to his almost mystical belief in the power of organizing.

Obama's banners tout CHANGE WE CAN BELIEVE IN, and this slogan cuts to the heart of the task before him. The key word isn't change, despite what legions of commentators have been saying all year. The key is believe. With gas prices up and home prices down; with Washington impotent to tackle issues like health care, energy and Social Security; with politics mired in a fifty-fifty standoff between two unpopular parties--plenty of Americans are ready to try a new cure. But will they come to believe that this new doctor, this charismatic mystery, this puzzle, is the one they can trust to prescribe it?

Convention 24/7 For constant updates and behind-the-scenes views from TIME's political reporters and photographers, go to time.com