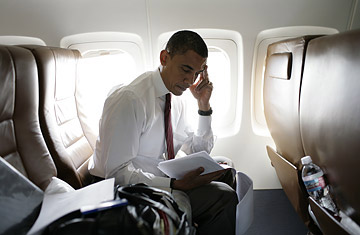

Senator Barack Obama looks over a speech on his campaign plane

(2 of 4)

The question, to borrow from Gates, is whether enough people in 2008 are ready to imagine such a thing. There's an interesting scene in Dreams in which Obama meets for the first time another of those influential elders--the Rev. Jeremiah Wright. Earlier this year, Wright's comments about race led Obama to repudiate his former pastor. In an uncanny way, this conversation from more than 20 years ago goes directly to the heart of Obama's current dilemma. The eminent sociologist William Julius Wilson had published a book arguing that the role of race in shaping society was giving way to class. But for Wright, the concept of a postracial politics simply didn't compute. "These miseducated brothers," the pastor fumed to the young Obama, "like that sociologist at the University of Chicago, talking about 'the declining significance of race.' Now, what country is he living in?"

If identity politics might gain some black votes for Obama, it can also cost him votes elsewhere. So how many Americans will agree with Wright that race is still front and center? The number is notoriously slippery, because voters don't always tell pollsters the truth. At the Weekly Standard, a magazine with a neocon tilt, writer Stanley Kurtz rejects Obama's postracial message because he suspects it isn't sincere. Probing the coverage of Obama's career as an Illinois legislator in the black-oriented newspaper the Chicago Defender, Kurtz concluded, "The politician chronicled here is profoundly race-conscious." Though Kurtz's message is aimed primarily at whites, it's not so different from one angrily whispered by Jesse Jackson. "I want to cut his nuts off," Jackson fumed--because he believes that Obama's race ought to determine which issues the candidate raises and how he discusses them. Either way, whether an opponent claims that Obama remains race-conscious or a supporter says he ought to be, both are rejecting the foundation of his campaign.

Figures like Jackson and Wright have invested a lifetime in the politics of black identity. Obama's success, whether it culminates in the White House or not, signals the passing of their era. So it is no wonder that younger voters have been key to his candidacy. Having grown up in the era of Oprah Winfrey, Denzel Washington, Tiger Woods and, yes, Henry Louis Gates Jr., they are better able to credit Obama's thesis that "there's not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there's the United States of America."

2. The Healer

Dreams from my father is the story of a quest--not for honor or fortune but for meaning. The book presents a wounded young man who has never felt entirely at home--not among whites or among blacks, neither in slums nor in student unions--and is haunted by "the constant, crippling fear that I didn't belong." He wants to know how to feel rooted and purposeful. At the end of his odyssey, he decides to take a leap of faith. For the young Obama, "faith in other people" becomes his home.

This is what he preaches: the seemingly unlimited power of people who are willing to trust, cooperate and compromise. Bringing people together for action, what he calls "organizing," holds "the promise of redemption." And without exactly saying it, Obama offers himself as the embodiment of his own message, the one-man rainbow coalition. You don't believe white and black can peacefully, productively coexist? Think the gulf between Chicago's South Side and the Harvard Law Review can never be bridged? Do you fear that the Muslim masses of Africa and Asia are incompatible with the modernity of the West or that cosmopolitan America and Christian America will never see eye to eye? Just look at me! It's not unusual to meet Obama supporters who say the simple fact of electing him would move mountains, changing the way the world looks at America, turning the page on the nation's racial history and so on. He is the change they seek.

The message doesn't work for everyone: so far, Obama's numbers in the national polls average below 50%. But his enormous and enthusiastic audiences are evidence that many people are intrigued, if not deeply moved. "Yes, we can!" turns out to be a powerful trademark at a time when 3 out of 4 Americans believe the country is on the wrong track. Many Democrats placed their political bets on anger in recent years: anger at the war, anger over the disputed election in 2000, anger at Bush Administration policies. Obama doubled down on optimism, beginning with his careermaking speech at the 2004 Democratic Convention: "Hope in the face of difficulty, hope in the face of uncertainty, the audacity of hope. In the end, that is God's greatest gift to us, the bedrock of this nation, a belief in things not seen, a belief that there are better days ahead."

If you click deeply enough into Obama's website, you can find position papers covering enough issues to fill Congressional Quarterly. He has a specific strategy to refocus the military on Afghanistan. He backs a single-payer health-care system. But it wasn't some 10-point plan that turned Obama into a politician who fills arenas while others speak in school cafeterias. He knows that detailed policies tend to drive people apart rather than bring them together. People arrived to hear him out of fervor or mere curiosity, and they stayed for the sense of possibility. They heard rhetoric like this, from his speech claiming victory after his epic nomination battle: "If we are willing to work for it and fight for it and believe in it, then I am absolutely certain that generations from now, we will be able to look back and tell our children that this was the moment when we began to provide care for the sick and good jobs to the jobless; this was the moment when the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal; this was the moment when we ended a war and secured our nation and restored our image as the last, best hope on Earth."

That's a pretty quick step from an election to nirvana, and Obama's opponents would like to turn such oratory against him. No one does it more effectively than radio host Rush Limbaugh, with his judo-master sense for his foes' vulnerabilities. Limbaugh rarely refers to Obama by his name. Instead, he drops his baritone half an octave and calls him "the messiah."

3. The Novice

Obama's critics tend to paint him two ways--related portraits but subtly different. The first is a picture of an empty suit, a man who reads pretty speeches full of gossamer rhetoric. "Just words," as Senator Hillary Clinton put it.