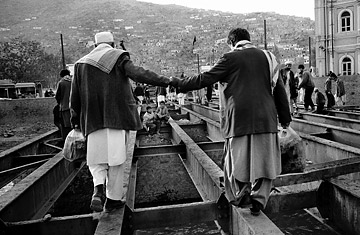

A LITTLE HELP FROM FRIENDS: Kabul residents cross an incomplete bridge. Infrastructure projects are the best way for the West to make a difference in the lives of Afghans

(3 of 3)

Our military strategy, meanwhile, should focus on counterterrorism--not counterinsurgency. Our presence has so far prevented al-Qaeda from establishing training camps in Afghanistan. We must continue to prevent it from doing so. But our troops should not try to hold territory or chase the Taliban around rural areas. We should also use our presence to steer Afghanistan away from civil war and provide some opportunity for the Afghans themselves to create a more humane, well-governed and prosperous country. This policy would require far fewer troops over the next 20 years, and they would probably be predominately special forces and intelligence operatives.

This strategy is far from ideal. But it's the best option we've got. It might not allow us to build an Afghan nation. It would involve a very long-term policy of containment and management, and it may never lead to a clear victory or exit. But unlike abandoning Afghanistan entirely, as we did in 1990, it would not leave a vacuum filled by dangerous neighbors. And unlike a policy of troop increases, this strategy would be less costly, more popular with voters, more sustainable in the long term, less of a distraction from other global priorities and less likely to alienate Afghan nationalists and undermine the Afghan state.

Transforming a nation of 32 million people is a task not for the West but for Afghans. Creating a narrative of national identity is not a technical engineering problem but more a question of mythmaking. Afghanistan's future must combine elders like Nabi with the aspirations of 5 million refugees, recently returned from Pakistan and Iran. And it will be influenced by even larger forces: the eddies of local ideologies, charisma, the fundamentals of population growth and natural resources, global commodity prices and the nation's relations with its neighbors, from Iran and Pakistan to China. It will draw on government bureaucracies and opaque tribal structures, on old constitutions and new cultures, on religion and luck. Afghans have the energy, the pride and the competence to lead that process. The West, however, does not. It should not waste its money, its lives and its reputation trying to do the impossible. It should invest in what it does well. We do not have a moral obligation to do what we cannot do.

Stewart lives in Kabul and is the author of The Places in Between and Prince of the Marshes. He was recently appointed the Ryan Professor and the director of the Carr Center for Human Rights at Harvard University