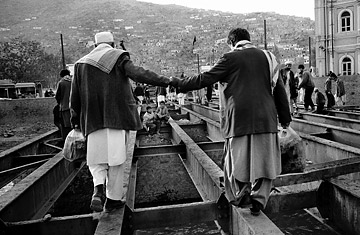

A LITTLE HELP FROM FRIENDS: Kabul residents cross an incomplete bridge. Infrastructure projects are the best way for the West to make a difference in the lives of Afghans

It is summer now in Kabul, the snow has largely melted from the 15,000-ft. (4,600 m) peaks, and I am sitting with my friends Hussein, Nabi and Zia in the garden of a 19th century fort. Nearby, 10 carpenters who work with my nongovernmental organization (NGO) are creating a library for a buyer in Tokyo. They're fitting slivers of wood into a delicate lattice and carving flowers into the walnut shutters. They work fast and smile often. But Nabi, a gentle-voiced 66-year-old cook, is not smiling. He is pessimistic about his country. "We have been promised progress by every government since 1973," he growls, "but it is getting worse and worse."

Nabi's pessimism is very common now in Afghanistan. There has been a dramatic series of recent attacks by the Taliban: a mass assault on a jail freed hundreds of prisoners, and a suicide bombing outside the Indian embassy on July 7 killed 40 and injured over 100. Many of these assaults are planned and supported from safe havens across the border in the tribal areas of Pakistan. Western troop casualties are climbing; the last two months exceeded the monthly death toll in Iraq. On July 13, nine U.S. soldiers were killed when Taliban fighters swarmed over their base in the eastern province of Kunar--the worst attack in three years.

But terrorism and insurgency are only part of what's going wrong in Afghanistan. In 2002, I walked safely along the length of the road between Herat and Obey in western Afghanistan. Recently aid workers were carjacked on that road, and it is now considered too dangerous for aid agencies, effectively closing the main access to the central regions of the country. In provinces close to Kabul, such as Wardak, Ghazni and Logar, which were easy to visit two years ago, foreigners are regularly attacked and girls' schools burned at will. Afghanistan produces 92% of the world's opium (used to make heroin) and 35% of its cannabis and has a flourishing trade in looted antiquities. In a vicious cycle, narcotics, corruption and the absence of law and order are rotting the heart of the government and crippling the economy. Despite massive Western investment, Afghanistan is close to being a failed state.

What should we do about it? Many policymakers want to throw more money and troops at the problem. Both Barack Obama and John McCain say that as President, they would send additional combat brigades--from 7,000 to 15,000 troops--to tame the insurgency in Afghanistan. At a June conference in Paris, Western governments committed an additional $20 billion in aid, in the hope that this would finally bring success in counterinsurgency, counternarcotics, rule of law, governance and state-building--and eventually allow us to withdraw from Afghanistan with honor.

But just because Afghanistan has problems that need to be solved does not mean that the West can solve them all. My experience suggests that those pushing for an expansion of our military presence there are wrong. We don't need bold new plans and billions more in aid. Instead, we need less investment--but a greater focus on what we know how to do.

What We've Done Right

When I walked across Afghanistan, shortly after the U.S.-led invasion had toppled the Taliban regime, there was no electricity in the 400 miles (640 km) between Herat and Kabul. The villages along the route were led by tribal chiefs, mullahs or guerrilla commanders who had little to do with their neighbors, let alone with the central government. Most districts that I visited had no schools or clinics. As a civil servant--I was on leave from my job in Britain's Foreign Office--I was surprised by how poor Afghanistan was and how ungoverned.

In 2006, after 11 months as a regional administrator in southern Iraq, I returned to Afghanistan to set up an NGO called the Turquoise Mountain to restore part of the old bazaar of Kabul and support traditional crafts. The garbage was then 7 ft. (2 m) deep in the streets, 200 yd. (180 m) from the presidential palace; there was no drainage, sewerage or water supply. Once famous traditional buildings were collapsing, and the craft-masters of ceramics, woodwork and jewelry were dying without passing on their skills. Most of the children in the area were not in school, most people were unemployed, few women were literate, and most of their children died before their first birthday.

The past six years, however, have made me optimistic about many aspects of Afghanistan. The community with which I work in the old city is hardworking, decisive and determined. In less than two years, we have cleared mountains of garbage, established clinics and primary schools, created jobs, restored the buildings and shops of the bazaar and attracted visitors and customers back into the area. I have been impressed also by the flexible and imaginative support that we began to receive from private philanthropists around the world and from Canadian and American development agencies.

There has been dramatic progress in many other parts of the country. Since 2001, 6.4 million children have been educated, and there has been a massive increase in access to basic health care. Western funding and assistance have helped create an efficient central bank, a stable currency, an elected parliament, telecommunications and infrastructure projects and a credible army. Some foreign aid goes directly into the hands of elected councils in over 20,000 villages, allowing them to initiate their own rural-development projects. Many of the villages I visited six years ago now have electricity and access to clinics and schools.

What's Gone Wrong

For all those improvements, however, it's clear why my friend Nabi is so pessimistic. The government has not established its authority or credibility. Civil servants lack the most basic education and skills. Perhaps a quarter of teachers are illiterate, and the majority are educated only one grade level above their students (if they are teaching second grade, they have a third-grade education). Many civil servants are corrupt. The police are notoriously predatory and violent. In much of the center and the north of the country, communities have benefited from small amounts of investment in development, health and education, but their contact with civil servants is minimal, and people remain very poor. In the south and the east, along the Pakistani border, the vacuum of government has become an opportunity for gangsters and the Taliban. These are the areas where almost all the world's opium is produced and where Western forces are fighting a costly counterinsurgency campaign.