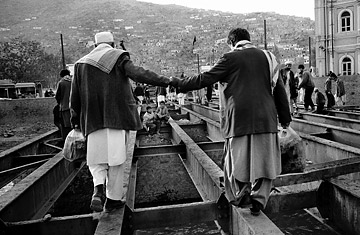

A LITTLE HELP FROM FRIENDS: Kabul residents cross an incomplete bridge. Infrastructure projects are the best way for the West to make a difference in the lives of Afghans

(2 of 3)

Many of these problems cannot be solved by the West, however many billions we spend or thousands of troops we deploy. Our money and expertise, which have helped make the central bank and the Afghan National Army professional and competent, cannot prevent the widespread corruption in the police and legal system. A central bank is relatively small, dealing with narrow issues such as currency and interest rates on which international economists can offer practical, technical advice. An army is able to develop its esprit de corps and drills in barracks, isolated from the broader society. But policemen and judges are much more connected to society and much more exposed to local politics and corruption. This is why most developing countries have relatively effective central banks and armies but corrupt and despised police forces. It's also why everyone finds it easier to build roads than to create rule of law, easier to build a school than a state. Afghans deal with most crimes outside the court system, using a traditional leader as an arbitrator. No amount of legal training can help a judge faced with drug lords who are prepared to kill his family. It is almost impossible for outsiders to reform this kind of system.

Fighting the Taliban is equally problematic. Western troops can win any conventional battle against ill-armed extremists, but both history and the latest doctrine on counterinsurgency suggest that ultimate victory will require control of Afghanistan's borders, hundreds of thousands of troops and a much stronger and more legitimate Afghan state, which could take Afghans decades to build. The West does not have the resources to match our ambitions in counterinsurgency, and we never will.

In any case, the preoccupations of the West--fighting terrorism and narcotics--are not the priorities of Afghans like Nabi, Zia and Hussein. Their major concerns are the state of the economy and basic services. Nabi has to keep working in a guesthouse kitchen at the age of 66 to feed his family. Like most other Afghans, he can barely afford bread: the price of flour has tripled in the past year as a result of a surge in global commodity prices. Unpredictable and uncontrollable events such as this may prove much more important than any international policy for the survival of the Afghan state. As Nabi says, "We are fed up with war. I am supporting five unemployed sons. Why can the government not create jobs?"

Getting Out of the Way

So what exactly should we do about Afghanistan now? First, the West should not increase troop numbers. In time, NATO allies, such as Germany and Holland, will probably want to draw down their numbers, and they should be allowed to do so. We face pressing challenges elsewhere. If we are worried about terrorism, Pakistan is more important than Afghanistan; if we are worried about regional stability, then Egypt, Iran or even Lebanon is more important; if we are worried about poverty, Africa is more important. A troop increase is likely to inflame Afghan nationalism because Afghans are more anti-foreign than we acknowledge and the support for our presence in the insurgency areas is declining. The Taliban, which was a largely discredited and backward movement, gains support by portraying itself as fighting for Islam and Afghanistan against a foreign military occupation.

Nor should we increase our involvement in government and the economy. The more responsibility we take in Afghanistan, the more we undermine the credibility and responsibility of the Afghan government and encourage it to act irresponsibly. Our claims that Afghanistan is the "front line in the war on terror" and that "failure is not an option" have convinced the Afghan government that we need it more than it needs us. The worse things become, the more assistance it seems to receive. This is not an incentive to reform. Increasing our commitment to Afghanistan gives us no leverage over the government.

Afghans increasingly blame us for the problems in the country: the evening news is dominated by stories of wasted development aid. The government claims that in 2007, $1.3 billion out of $3.5 billion of aid was spent on international consultants, some of whom received more than $1,000 a day and whose policy papers are often ignored by Afghan civil servants and are invisible to the population. Our lack of success despite our wealth and technology convinces ordinary Afghans to believe in conspiracy theories. Well-educated people have told me that the West is secretly backing the Taliban and that the U.S.'s main objective was to steal Afghanistan's emeralds, antiquities and uranium--and that we knew where Osama bin Laden was but had decided not to catch him.

Playing to Our Strengths

A smarter strategy would focus on two elements: more effective aid and a more limited military objective. We should target development assistance in provinces where we have a track record of success. Our investment goes further in stable and welcoming places like Hazarajat than it can in hostile, insurgency-dominated areas like Kandahar and Helmand, where we have to spend millions on security and the locals do not contribute to the project and will not sustain it after our departure. We should focus on meeting the Afghan government's request for more investment in agricultural irrigation, energy and roads. And we should increase our support to the most effective departments, such as education, health and rural development; they are good for the reputation of the Afghan state and the West. Creating more educated, healthier women and men and better transport, communications and electrical infrastructure may be only part of the story, but they are essential for Afghanistan's economic future.

Our efforts in nation-building, governance and counternarcotics should be smaller and more creative. This is not because these issues are unimportant; they are vital for Afghanistan's future. But only the Afghan government has the legitimacy, the knowledge and the power to build a nation. The West's supporting role is at best limited and uncertain. The recent elimination of the opium crop in Nangarhar, for instance, was driven by the will and charisma of a local governor and owed little to Western-funded "capacity-building" seminars. The greatest recent improvements in local government have come about through the replacement of local governors rather than through hundred-million-dollar training programs. Since these successes are often difficult to predict, we should invest in numerous smaller opportunities rather than bet all our chips on a few large programs.