(3 of 3)

Most experts also agree on the list of tools available for closing the debt gap. Raising taxes, cutting spending — or some combination of both. Inflation can be another tool: when it goes up, the value of existing debt goes down. For example, $100 borrowed in 2000 is worth less than $80 now, thanks to inflation's slow erosion. Speed up that erosion a bit and debt melts away. There's a downside, though: savings melt away too.

The last tool is everyone's favorite because it's all pleasure and no pain: economic growth. If the $15 trillion U.S. economy grows by 3% rather than 2% per year, after a decade that extra percentage point will mean almost $2 trillion extra in the national wallet each year. But how do you get faster growth? That question is the big enchilada, and if Ryan has his way, it's the one voters will answer next year. In broad terms, today's conservatives believe that relatively low taxes, low government spending and low inflation are the seeds of higher growth rates. Republicans had a chance to test this theory during the George W. Bush years but skipped the low-spending part. In contrast, today's Democrats — again, speaking broadly — believe higher taxes on the wealthy can fund federal investments that promote economic opportunity and innovation.

For all the rhetoric about greedy skinflints and wild-eyed socialists that we're likely to hear next year, the real dispute over our fiscal future boils down to which tools to use and how aggressively to use them. Ryan opened the bidding by drawing nothing from Column A and trillions from Column B. His proposal called for tax reform but not higher tax revenues. On the other hand, Ryan would freeze all nonsecurity discretionary spending. Washington would stop running Medicaid, the program for indigent patients. Instead, the federal government would send checks to the states to set up their own programs. Though his plans don't specify changes to Social Security, Ryan favors payments based on need rather than preretirement earnings. And future retirees (people under 55 now) would buy their own health insurance, only partly subsidized by the government. Medicare in its current form, which pays doctors and hospitals directly for services, would go away. Here again, Ryan would provide larger subsidies for poorer patients.

There's a lot for Democrats to attack in that plan. As the saying goes, everything in the federal budget is there because someone likes it. But Ryan believes talking about dramatic change is the first step toward "detoxifying these issues." He says, "People are waking up, turning on the TV, seeing their states struggling with debt problems, seeing Europe implode, and they are realizing that something different needs to happen."

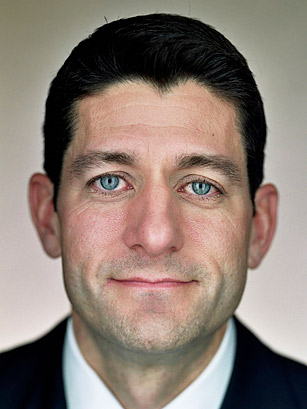

When I visited him at his Washington office shortly after Thanksgiving, the usually clean-shaven Republican was still sporting a goatee from deer-hunting season. He's an outdoorsman, which he gets from his mother, and a fitness buff, unlike his dad. Ryan was a teenager when he found his father, a Janesville attorney, dead of a heart attack in his 50s; his grandfather also died young of a heart attack. Ryan seems determined to break the grim history. Congressional staffers have voted him the Hill's No. 1 gym rat.

Asked why he didn't put his hat in the ring, Ryan answers, "I have the policy ambition. I just don't have the personal, political ambition" that it takes to be President. "You have to want it so badly in your heart, your mind and your stomach. I don't have that fire in my gut."

What Ryan had this year was the courage to look the future in the eye. It is a seer's work to glimpse around the corner and sound an alarm. And in a democratic republic, it is the job of voters to choose a path away from danger. Ryan would say that all he has done is sound the alarm. The hard work — and some hard years — remains, because for all the shocking and unsettling changes embodied in Ryan's proposal, it wouldn't balance the federal budget until 2040. The prophet of 2011 will be 70 years old.