(2 of 3)

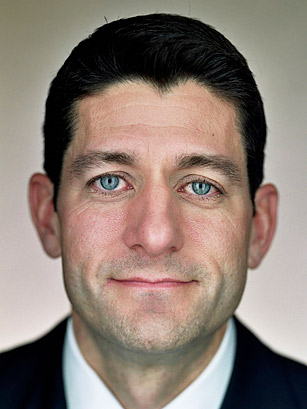

Ryan was just 28 when he entered Congress in 1999. The budget was balanced. The stock market was booming. But he was fixated on the impossible arithmetic of the U.S.'s long-term fiscal commitments: health care inflation x (more retirees + longer life spans) = 1 big problem. So he worked his way up the Budget Committee ladder, following advice he was given by the liberal Barney Frank of Massachusetts: the way to have an impact in Congress is to "be a specialist, not a generalist."

From his seat on the committee, Ryan watched his party's leadership inflate the deficit by cutting tax rates like Kemp conservatives while spending like Kardashians. When in 2008 he had reached a position in which he could introduce his own sobering budget resolution, he called it the Roadmap for America's Future. It looked very different from the recent Republican past, and he picked up just eight co-sponsors. Ryan figured that "we just have to persevere on the politics — everyone is so afraid of the politics of these issues." It's fun to cut ribbons on buildings and smile for the cameras while handing out checks. Voting for cuts is no fun at all. "That's why paralysis set in," he says. "And the problems just got bigger."

Undeterred, Ryan ran his road map up the flagpole again in 2010, this time with 14 co-sponsors. That caught the eye of the Tea Party movement, which had loads of energy and was looking for places to channel it. Ryan, now in his seventh term, became an overnight sensation — a darling of Fox News and Rush Limbaugh, with big donors begging him to run for President, while his plan (renamed the Path to Prosperity) sailed through the House with 235 Republican votes. Though it stalled in the Senate, where Democrats have a majority, Ryan's plan won 40 Republican votes.

Democrats were likewise galvanized. "One of the worst things to happen to this country," Senate majority leader Harry Reid declared it. A "path to poverty," House minority leader Nancy Pelosi preferred. The President invited Ryan to sit front and center for an April 13 speech outlining his own budget priorities. Also invited were Democrat Erskine Bowles and Republican Alan Simpson, co-chairs of a bipartisan commission on fiscal reform. The President's staff, Ryan says, "led us to believe" that the speech would be a first step toward a compromise that would put the budget on firmer footing. Instead, Ryan walked into an old-fashioned setup: Obama delivered a blistering denunciation of Ryan's plan in full-throated campaign mode. Points of agreement were ignored, points of disagreement highlighted, even distorted. "I don't think there's anything courageous," Obama charged, "about asking for sacrifice from those who can least afford it." It was at about that moment, Ryan realized, that he and his plan had become a central issue in the 2012 elections. "That's when the lightbulb went off," Ryan explains. "They were constructing a political plan."

The points of agreement are worth noting, even if the politicians won't do it. Ryan's dramatic proposal would not have gained any traction if it did not address a widely acknowledged problem: over the next two generations, the U.S. government is on track to spend many tens of trillions of dollars more than it plans to raise. Unless changes are made, that will force so much borrowing that interest payments alone will sink the federal budget.

That dismal prospect has been with us for years but was always distant enough to make it easy for most people to ignore. That was before the economy went haywire and Greece, Spain and Italy turned into cautionary tales. "I used to talk about the problems we would have in 10 years. That was before the recession." Now, Ryan says, "The experts are telling us the point of no return is two to five years out, maybe just two or three. Everything is moving faster, pushing us closer to the cliff."